化感作用(Allelopathy)是植物在长期进化的过程中形成的一种适应机制, 有利于保持本物种在空间和资源竞争中的优势[1]。植物释放到环境中的化感物质(Allelochemical)通常为次生代谢产物(如酚酸类化合物、萜类化合物以及炔类化合物等), 几乎可以由植物的任何组织或器官合成, 例如植物根、茎、叶、果实、种子等[2-3]。这些化感物质进入环境后能够影响周围植物的生长发育。

植物化感作用与植物自身的生长特性有关。由于植物固着生长, 其无法通过移动来逃避逆境, 只能通过改变自身形态结构以及生理生化反应来适应环境, 或者通过释放化学物质来影响周边其他植物的生长发育, 以改变微环境, 使环境向着更适合自己生长的方向发展[4-5]。桉树(Eucalyptus robusta)人工林中植被比较稀少[6-7], 大豆(Glycine max)连作会导致严重减产[8-9], 外来植物可能造成生物入侵[10]。这些现象都是植物之间化感作用的表现。

种子萌发是植物生命周期中的关键环节, 对植物生长发育至关重要[11-12]。在农业生产方面, 种子的正常萌发与出苗对作物产量影响很大[13]。种子萌发率或者出苗率下降都会导致作物有效株数下降, 进而导致产量降低[14]。因此研究化感物质对种子萌发的影响具有重要意义。本文针对化感作用的最新研究进展进行综述, 阐述化感物质调控种子萌发的机理, 并探讨其生态学意义, 以期为该领域今后理论研究以及生产实践提供借鉴。

1 化感作用 1.1 化感作用定义的发展历史上, 人们就注意到植物之间存在相生相克的现象, 如黑胡桃(Juglans nigra)树下其他植物很难生存, 鹰嘴豆(Cicer arietinum)可显著抑制杂草生长[3], 但其背后的具体机理一直不甚明了, 直到最近几十年, 随着相关研究的逐渐增多, 才取得了重要进展。1937年, Molisch将这种植物(包括微生物)之间有益或者有害的化学相互作用定义为化感作用[15]。随后, 在20世纪70年代, Rice进一步完善了化感定义, 即植物(包括微生物)释放化学物质进入环境中, 并对其他植物产生直接或间接的有害作用[16]。后来, 植物之间相互促进生长及自毒现象也被纳入化感作用范畴[17-18]。1996年, 国际化感学会将化感作用定义为:植物、细菌、真菌以及藻类的次生代谢产物对农业以及自然生态系统生物的生长发育产生的影响[19]。

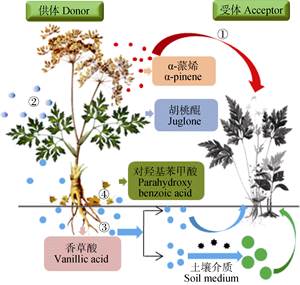

1.2 化感物质分类及进入环境的途径Rice将化感物质分为14类, 分别是水溶性有机酸、直链醇、脂肪族醛和醇, 简单不饱和内酯, 长链脂肪酸和多炔, 萘醌、蒽醌以及复杂醌类, 简单酚、苯甲酸及其衍生物, 肉桂酸及其衍生物, 单宁, 萜烯和甾族化合物, 氨基酸和多肽, 生物碱和氰醇, 硫化物和芥子油苷, 嘌呤和核酸, 香豆素以及类黄酮[18]。这些化感物质可以通过自然挥发、根系分泌、雨雾淋溶以及植株腐解4种方式进入环境[20-21], 影响临近植物生长, 以确保自身获得足够的资源(图 1)。

|

图 1 植物化感物质进入环境的4种途径 Figure 1 Four ways of plant allelochemicals entering into the environment 图中编号表示化感物质进入环境的途径: ①自然挥发; ②雨雾淋溶; ③根系分泌; ④植株腐解。其中α-蒎烯、胡桃醌、香草酸以及对羟基苯甲酸分别代表以上4种方式释放入环境中的典型化感物质。图中红色箭头表示供体植物释放挥发性化感物质直接作用于受体植物; 蓝色箭头表示供体植物释放的化感物质进入土壤后作用于受体植物; 绿色箭头表示供体植物释放的化感物质进入土壤, 在土壤介质的作用下发生改变(化感物质被活化或者被转变为其他物质)后作用于受体植物。This figure shows the four ways by which plant allelochemicals enter into the environment. ① indicates volatilization; ② indicates leaching; ③indicates rootexudation; and ④ indicates decomposition of plant residues in soil. In this figure, α-pinene, juglone, vanillic acid and parahydroxy benzoic acid are the typical allelochemicals released into the environment through the above four ways, respectively. Red arrow indicates that the donor plants release volatile allelochemicals acting on the acceptor plant directly. Blue arrow indicates that the allelochemicals released by the donor plant act on the acceptor plants after entering into the soil. Green arrow indicates allelochemicals released by the donor plants change (activated or converted into other substances) in soil, and then act on the acceptor plant. |

化感物质对植物种子的影响分为两个方面。一方面, 化感物质抑制种子萌发; 另一方面, 化感物质能促进种子萌发。目前, 多数研究集中在化感物质抑制植物种子萌发方面[22-24]。此外, 化感物质对种子萌发表现为促进还是抑制, 与化感物质种类、浓度以及受体植物种类有很大关系[25-27]。

2.1 化感物质抑制植物种子萌发许多化感物质能显著抑制植物种子萌发, 并影响种子萌发后幼苗的生长发育。对加拿大一枝黄花(Solidago canadensis)的研究表明, 其地上部的水提取液能显著抑制鸡眼草(Kummerowia striata)、莴苣(Lactuca sativa)、萝卜(Raphanus sativus)等种子的萌发, 根部的水提取液亦能显著抑制鸡眼草种子的萌发, 但是对莴苣以及萝卜种子萌发影响不显著[10, 28]。这表明, 同一植株的不同部位产生的化感物质对不同植物种子萌发的生理效应有所不同。与加拿大一枝黄花类似, 生姜(Zingiber officinale)的茎和叶的水提取液在多个浓度下均能抑制大豆及北葱(Allium schoenoprasum)种子萌发, 但不同部位的提取液抑制效果有所差异[29]。对金银忍冬(Lonicera maackii)的化感作用研究表明, 植物的化感抑制效应与化感物质的浓度有关。金银忍冬叶片和根的水提取液对葱芥(Alliaria petiolata)以及拟南芥(Arabidopsis thaliana)种子的萌发均有抑制作用, 且抑制效应随着提取液浓度升高而更加明显[27]。

进一步的研究表明, 在同一植物提取液中, 不同成分的化感物质对种子萌发的抑制作用也不相同。对烟草(Nicotiana tabacum)根系渗出液中含有的6种有机酸(苯甲酸、肉桂酸、月桂酸、肉豆蔻酸、软脂酸以及邻苯二甲酸)的研究表明, 相同浓度下苯甲酸和肉桂酸对烟草种子萌发的抑制作用最明显[25]。但是, 并非所有化感物质都会降低种子萌发率, 有些仅仅是延缓种子的萌发进程。相关研究表明, 美国杜鹃(Rhododendron maximum)、山月桂(Kalmia latifolia)以及金银忍冬叶片提取液对苇状羊茅(Festuca arundinacea)种子的最终萌发率无明显影响, 但是能显著延缓其种子的萌发进程, 即对照组种子萌发率于第8 d即达到最大值, 而处理组在12 d才达到最大值[30]。此外, 一些植物会表现出很强的自毒作用[31-33]。研究表明, 连续种植三七(Panax notoginseng)的土壤能显著抑制三七种子萌发, 且随种植年限延长, 抑制效果越明显[31]。以上研究表明, 化感物质对植物种子萌发具有强烈的抑制作用, 且这种抑制作用与植物种类、植物不同部位以及化感物质浓度有关。

2.2 化感物质促进植物种子萌发虽然大多数化感物质表现为抑制其他植物种子萌发或者强烈的自毒作用, 但是部分化感物质也会促进其他植物种子的萌发。对14个大豆栽培品种的化感作用研究表明, 大豆三节期根、茎以及叶的甲醇提取液均能显著促进向日葵列当(Orobanche cumana)种子萌发, 其中根部提取液的促进效果最明显[34]。与此类似, 玉米(Zea mays)、小麦(Triticum aestivum)、马铃薯(Solanum tuberosum)、大麻(Cannabis sativa)以及棉花(Gossypium hirsutum)的根际土或者植株提取液能显著提高列当属植物的种子萌发率[35-39]。同时, 麻风树(Jatropha curcas)的叶片水提取液对芝麻(Sesamum indicum)种子的萌发起促进作用[40], 小麦和大豆根部渗出原液则能显著提高黄瓜(Cucumis sativus)种子萌发率[26]。

化感物质促进植物种子萌发, 是植物之间相互协作的一个范例, 有助于植物生长发育。但是, 这种促进作用对于寄主植物可能是有害的, 一旦寄主植物释放化学物质刺激寄生植物种子萌发, 寄主植物本身的生长就会受到影响。在农业生产上, 可以将玉米或大豆与向日葵列当的寄主植物[例如甜瓜(Cucumis melo)、豌豆(Pisum sativum)、蚕豆(Vicia faba)以及烟草等]进行间套作或者轮作, 玉米或大豆可以释放化感物质诱导向日葵列当种子萌发, 而萌发的向日葵列当又不能寄生在玉米或大豆植株上, 最后, 向日葵列当便会因缺少营养而死亡, 从而降低向日葵列当地下种子库, 减少对寄主植物的危害[34-35]。

3 化感物质调控植物种子萌发的机制 3.1 抑制胚的生长种胚是由受精卵发育而成的植物幼体, 是种子的重要组成部分。植物种子吸水膨胀, 胚根突破种皮和胚乳后, 即为种子萌发[41]。因此, 化感物质能通过抑制胚的生长而抑制种子萌发。

研究显示, 生姜茎和叶的水提液能抑制大豆和北葱胚根以及下胚轴的生长, 且这种抑制效果随着提取液浓度升高而增强[29]。与此类似, 黑芥(Brassica nigra)的根、茎、叶以及花的水提取液亦能抑制野燕麦(Avena fatua)胚根和下胚轴的伸长, 其中胚根对化感物质最为敏感[42]。但并非每类化感物质都能通过同时抑制胚根和下胚轴的伸长来抑制胚的生长。比如, 芳香植物灌木鼠尾草(Salvia leucophylla)挥发物中的单萜类物质(樟脑、1, 8-桉叶素、α-蒎烯、β-蒎烯、莰烯)能显著抑制油菜(Brassica campestris)胚根的生长, 但是对下胚轴没有显著影响; 进一步研究结果显示, 单萜类物质能通过抑制胚根顶端分生组织细胞的增殖, 从而抑制胚根生长[43]。土荆芥(Dysphania ambrosioides)挥发油能诱导蚕豆根尖细胞染色体发生畸变, 导致DNA合成受阻, 降低细胞有丝分裂指数, 从而导致胚根生长受到抑制, 而且这种抑制效果具有明显的浓度效应以及时间效应[44]。由此可见, 化感物质能通过抑制胚的生长, 阻碍胚根突破种皮, 从而抑制种子萌发。

3.2 对细胞结构的影响种子萌发过程中, 幼胚细胞数目增加, 体积增大, 而完整的细胞结构对于这个过程是必需的。研究表明, 化感物质会作用于细胞, 破坏细胞结构, 进而影响植物种子萌发。

向日葵(Helianthus annuus)叶片提取液处理白芥(Sinapis alba)种子, 会导致白芥种子中电解液渗透率增加, 丙二醛(malondialdehyde, MDA)含量升高, 细胞膜受到严重破坏[21]。Sicyos deppei叶片提取液处理菜豆(Phaseolus vulgaris)种子, 导致菜豆胚根根冠细胞液泡内陷, 染色体紊乱, 核仁变小; 根边缘细胞排列紊乱, 细胞壁以及液泡形状不规则[45]。与此类似, 土荆芥挥发油诱导蚕豆根尖细胞核染色体畸变, 导致细胞微核率显著增加, 细胞分裂受阻, 同时, 加剧细胞凋亡[44]。因此, 化感物质能通过影响细胞结构, 干扰细胞正常生命活动, 来抑制植物种子萌发。

3.3 干扰种子中活性氧的产生与积累活性氧(reactive oxygen species, ROS)是生物有氧代谢过程中产生的一类小分子, 参与细胞内许多重要的生理过程。一方面, 作为重要的信号分子, 活性氧在种子萌发以及植物抗逆性方面具有重要的调控作用[13, 46-47]。另一方面, 细胞内积累过多的活性氧则会破坏细胞膜以及细胞内大分子物质, 影响植物生长发育以及种子萌发[48-49]。已有研究表明, 环境胁迫会干扰植物细胞内部稳态, 促进活性氧积累[48]。而作为一种生物胁迫, 化感作用能影响植物种子萌发过程中活性氧的产生与消除, 进而调控植物种子萌发[50]。

种子萌发过程中, 活性氧的产生与清除处于动态平衡中, 但受到化感胁迫时, 这种平衡关系被打破, 种子萌发就会受到抑制。高浓度的香豆素能通过干扰小麦种子中超氧化物歧化酶(superoxide dismutase, SOD)、脱氢抗坏血酸还原酶(dehydroascorbate reductase, DHAR)和单脱氢抗坏血酸还原酶(monodehydroascorbate reductase, MDHAR)等抗氧化酶的活性, 以及抗坏血酸(ascorbic acid, AsA)和谷胱甘肽(glutathione, GSH)等抗氧化剂的含量, 进而影响小麦种子萌发过程中活性氧的含量, 抑制小麦种子萌发[51]。用向日葵叶片提取液处理白芥种子后, 白芥种子中H2O2的含量显著升高, 谷胱甘肽还原酶(glutathione reductase, GR)活性受到明显抑制, 虽然处理后期GR、SOD以及过氧化氢酶(catalase, CAT)的活性都有所增加, 但是白芥种子中H2O2含量仍然持续升高, 细胞膜受到破坏, 种子萌发受到抑制[21]。

很多化感物质会导致植物体内活性氧含量增加, 进而造成细胞死亡, 从而影响植物生长发育。非常有趣的是, 对黄酮类化合物Myrigalone A的相关研究表明, Myrigalone A能抑制家独行菜(Lepidium sativum)种子中活性氧的产生, 从而阻碍细胞分裂, 抑制胚根生长, 进而抑制种子萌发[52-53]。虽然大多数化感物质对于植物种子萌发具有抑制作用, 但是不同的化感物质抑制种子萌发的途径有所差异, 因此非常有必要深入研究每类化感物质对种子萌发的具体作用机理。

3.4 影响种子萌发过程中的代谢途径植物种子吸胀完成后, 进入萌动阶段, 这时吸水量减少, 但是种子内部生理生化反应异常活跃, 随后种子胚根生长突破种皮, 种子萌发[41, 50]。化感物质可通过干扰种子萌发阶段内部的生理生化反应来抑制植物种子萌发。

6-甲氧基-2-苯并唑啉酮(6-methoxy-2-benzoxazolinone, MBOA)对小麦、水稻(Oryza sativa)、黑麦(Secale cereale)、莴苣以及野胡萝卜(Daucus carota)等植物种子萌发具有显著的抑制作用[54]。进一步研究结果表明, MBOA能抑制α-淀粉酶活性, 降低种子中淀粉的转化利用效率, 进而抑制植物种子萌发[54-55]。与此类似, 生姜茎和叶的水提液均能抑制大豆或者北葱种子中脂肪酶活性[29]。化感物质不仅阻碍种子萌发过程中物质的转化, 同样也干扰其能量代谢。向日葵叶片水提液不仅能抑制白芥种子中肽链内切酶(endopeptidase)以及异柠檬酸裂解酶(isocitratelyase, ICL)的活性, 干扰种子内部储存蛋白以及脂肪酸的降解, 而且阻碍O2吸收, 抑制ATP的产生, 干扰种子内部能量代谢, 进而抑制种子萌发[56]。植物种子萌发初期会动用种子内部储存的蛋白质、油脂或者淀粉来获取能量, 并进行活跃的物质合成, 以满足种子萌发所需要的物质和能量; 而化感物质正是通过干扰种子萌发过程中的物质代谢以及能量代谢来抑制植物种子萌发。

3.5 打破种子内源激素平衡植物种子的萌发受到一系列机制的调节, 从而保证幼胚的正常生长[57]。在众多调节种子萌发的机制中, 激素扮演着重要的角色。常见的植物激素包括脱落酸(abscisic acid, ABA)、生长素(auxin)、乙烯(ethylene, ETH)、赤霉素(gibberellin, GA)、细胞分裂素(cytokinin, CTK)以及油菜素甾醇(brassinosteroid, BR), 它们共同协同或拮抗调控着植物生长发育, 其中ABA、GA、ETH以及生长素能调控种子萌发[14, 58-60]。

研究表明, GA促进种子萌发, 而ABA抑制种子萌发[61-62]。环境因子通过调节与两种激素生物合成与分解代谢相关酶的生物活性来控制两者的比例, 进而调控植物种子的萌发[63]。Myrica gale是一种生长在河边、湖边或者沼泽潮湿地带的落叶灌木[64], 其果实和叶片中含有一种黄酮类化感物质Myrigalone A能显著影响其他植物种子的萌发[53, 65]。Myrigalone A能显著抑制家独行菜种子的胚乳破裂以及胚根伸长, 进而抑制其种子萌发[52-53]。进一步研究表明, Myrigalone A对ABA含量没有显著影响, 但是能抑制家独行菜种子幼胚中GA3氧化酶的活性, 干扰GA代谢及信号转导, 进而影响GA与ABA比值, 从而抑制其种子萌发[52]。与此类似, 在对向日葵化感作用的研究表明, 向日葵叶片提取液能提高白芥种子中ABA的含量, 并通过干扰ACC氧化酶以及ACC合成酶的活性来降低ETH含量, 进而抑制白芥种子萌发[66]。综上所述, 化感物质能影响植物种子萌发过程中激素的含量, 打破种子内源激素平衡, 从而抑制种子萌发。

4 化感物质影响种子萌发的生态学意义 4.1 抑制杂草种子萌发在农业生产中, 杂草是造成作物减产的主要因素之一, 如何科学地控制杂草, 提高作物产量, 是一个重要的生产问题。目前, 化学合成除草剂在抑制杂草方面扮演重要角色, 能显著提高作物产量, 但是它对作物和环境具有不利影响, 威胁人类健康[67-69]。近年来, 已经发现很多作物能释放化感物质进入环境, 抑制杂草生长[70-75]。事实上, 作为一种天然的化学除草剂, 化感物质的抑草作用在农业生产上受到了越来越多的关注[2, 76]。化感物质是由植物或者微生物产生的一种天然的化合物, 可以在环境中被生物降解。合理利用作物的化感作用或者以化感物质部分代替化学合成除草剂, 对于保护环境, 实现农业可持续发展具有重要意义[77-78]。

将能释放化感物质的作物与其他作物进行间作、套作或者轮作, 能改善农田土壤性质, 抑制杂草生长, 提高作物产量[79-80]。草木犀(Melilotus officinalis)是一种优良的饲草和绿肥, 在与豌豆(Pisum sativum)、亚麻(Linum usitatissimum)以及芥菜(Brassica juncea)套作收获后, 草木犀的残株能显著降低杂草密度, 抑制蒲公英(Taraxacum mongolicum)、苦菜(Lobelia davidii)、地肤(Kochia scoparia)、藜(Chenopodium album)、旱雀麦(Bromus tectorum)等杂草种子萌发, 其中对藜及地肤两种杂草密度的抑制率达到80%, 并显著降低野燕麦的生物量[81-82]。与此类似, 经济作物菊芋(Helianthus tuberosus)的茎和叶混合基质能显著降低杂草密度[83]。因此, 利用作物之间的化感作用, 合理搭配农作物种植方式, 有利于抑制农田杂草, 提高作物产量, 同时保护生态环境。

4.2 生态系统中的化感作用生态系统是指在一定时间和空间内, 生物群落与环境构成的统一整体, 在这个统一整体中, 生物与环境之间相互影响、相互制约, 并在一定时期内处于相对稳定的动态平衡状态。生态系统中每种植物都有自己特定的分布区域, 植物之间相互影响, 共同形成稳定的群落分布格局。

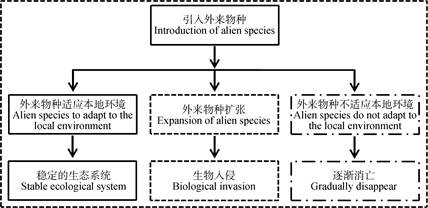

4.2.1 生物入侵引入外来物种会导致3种结局:外来物种不适应引入地环境而逐渐消亡、与引入地物种共同形成稳定生物群落以及造成生物入侵(图 2), 其中生物入侵会对入侵地区的生态系统造成严重威胁[84]。生物入侵是指生物由原生存地经自然或人为途径侵入到另一个新的环境, 对当地的生物多样性、自然环境以及经济造成损失。很多植物在离开自己原先的生活环境后, 会表现出极强的侵入能力, 例如加拿大一枝黄花[85]、微甘菊(Mikania micrantha)[86]、豚草(Ambrosia artemisiifolia)[87]以及紫茎泽兰(Ageratina adenophora)[88]等。但是, 外来入侵物种在原有生态系统中不会造成生物入侵, 其中很大一部分原因是在原有生态系统经过上百年甚至上千年的协同进化, 相互之间达到一种和谐共生状态。一旦这种和谐共生格局被打破, 生物之间相互制约关系被破坏, 就容易造成生物入侵。导致生物入侵的原因有很多, 化感就是其中一个方面。

|

图 2

外来物种进入本地生态系统后的3种发展方向

Figure 2

Three types of destiny after alien species entering into the local ecosystem

实线框表示外来物种与当地物种共同建立稳定的生态系统; 虚线框表示外来物种造成生物入侵; 点划线框 |

很多外来入侵物种都能释放化感物质影响其他植物生长, 从而增强竞争资源的能力, 保证自身生长[89-90]。研究表明, 紫茎泽兰地上部凋落物的不同浓度水提液均能抑制紫花苜蓿(Medicago sativa)和白三叶(Trifolium repens)种子萌发及幼苗生长[91]。在对生长于原生地(北美)以及侵入地(中国)的加拿大一枝黄花进行比较发现, 在侵入地生长的加拿大一枝黄花地上部或地下部提取液中酚类化合物、黄酮类化合物以及皂苷都显著或者极显著高于原生地生长的加拿大一枝黄花, 同时, 两者的提取液均能显著抑制鸡眼草种子的萌发, 并且侵入地生长的加拿大一枝黄花的抑制作用更明显[5]。外来侵入物种在侵入地能释放更多化感物质进入周围环境, 影响周围植物生长发育, 从而为自己迅速蔓延创造条件。一旦外来物种在侵入地大规模繁殖, 就会导致当地生态结构单一, 本地生物多样性减少, 容易引发当地生态危机[92]。

4.2.2 对生态系统中群落组成与分布格局的影响虽然外来入侵植物会通过释放化感物质影响其他植物生长, 造成生物入侵, 对当地生态系统稳定性造成威胁; 但另一方面, 化感作用对于维持生态系统中群落的组成与分布格局具有重要意义。其中最典型的一个例子, 就是对美国南加州灌木丛的化感作用的研究, 研究者发现, 在每块灌木丛的周围都会出现1~2 m的裸带, 这些裸带中没有任何植物。进一步研究发现, 灌木释放的萜类化合物能随着雨雾进入周围环境中, 抑制草本植物种子萌发及幼苗生长, 从而形成这种稳定的分布格局[93]。

自毒作用是化感作用的一个重要方面, 是指一种植物释放化感物质抑制同类植物种子萌发及植株生长的现象[94]。研究表明, 天山云杉(Piceaschrenkiana)、杉木(Cunninghamia lanceolata)、紫花苜蓿以及马铃薯等植物都具有明显的化感自毒作用[95-98]。例如, 油松(Pinus tabuliformis)根和叶的水提取液以及乙酸乙酯提取液对油松种子萌发及幼苗生长具有明显的抑制作用, 此外, 油松挥发油亦能显著抑制油松种子萌发及幼苗生长[99]。对杉木自毒作用的研究表明, 杉木根、鲜叶、枯叶、半分解枯叶以及根际土壤浸提液对杉木种子萌发及幼苗生长均有不同程度的抑制作用, 其中杉木根际土壤以及非根际土壤浸提液对杉木种子萌发的抑制作用随着杉木栽植代数增加而更加明显[100-101]。

在生态系统中, 具有自毒作用的植物能释放化感物质抑制同种植物种子萌发与幼苗生长, 起到自疏的作用。植物通过这种方式降低种群密度, 一方面避免了过多幼苗竞争养分与资源, 影响成株生长; 另一方面, 避免同一地区形成单一植物群落, 从而增加地区生物多样性, 稳定生态系统。自毒作用是植物对环境的一种适应机制, 有利于生态系统的稳定与发展。但是在生产实践上, 自毒作用会导致严重的减产。现在已经发现很多经济作物、粮食作物以及园艺植物, 都存在着严重的自毒作用[9, 31, 102-103]。尽管自毒作用是植物与环境长期作用的结果, 在生产实践上我们也无法避免, 但是我们可以通过合理的种植制度安排减少自毒作用造成的损失[104]。例如, 可以将作物合理的间混套作或者轮作, 避免化感自毒作用; 育种工作者可以选育优良抗自毒作物品种; 在园艺植物方面, 可以选择优良砧木进行嫁接; 也可以通过合理施肥的方式减轻化感自毒作用。

5 展望尽管人们很早就注意到植物之间的化感作用, 但是直到最近几十年才真正重视化感作用的研究。而化感物质对植物种子萌发的影响作为本领域的重要方面, 近年来取得了一些重要的进展。在已有研究的基础上, 特提出以下重点研究方向及建议。

首先, 在自然界中, 化感物质一般是溶于雨水后进入环境, 进而影响植物种子萌发和植物生长。然而, 在目前的很多研究中, 常使用甲醇、乙酸乙酯以及丙酮等有机溶剂提取植物组织内的化感物质, 这种提取方法虽然可以将化感物质提取出来, 但是这样也会把植物内部的非化感物质提取出来, 而且提取浓度与自然界中也会有差异。这也是为什么有些试验表明某些植物具有化感作用, 但是在自然界中化感作用不是很明显, 其中一个原因就是提取液中有很多物质不是化感物质。因此, 在之后的试验中, 提取化感物质尽量以水为介质, 模拟自然界中化感物质进入环境的形式, 这样才能更好更准确地解释化感现象。

其次, 化感物质可以通过4种方式进入环境, 除了自然挥发之外, 其余3种途径释放的化感物质都会随着雨水进入土壤, 然后作用于临近植物。化感物质进入土壤以后, 在土壤微生物以及土壤介质的作用下, 会发生一些改变, 同时, 化感物质也会影响土壤微生物的群体结构以及土壤环境。不同的化感物质进入土壤以后会发生怎样的变化以及不同的化感物质会影响哪些特异的微生物的群体结构?深入研究这些科学问题对于理解连作障碍以及化感抑草作用具有重要的理论与实际意义。

再次, 已有研究表明, ABA、GA、ETH等激素以及ROS在种子萌发过程中具有重要的调节作用, 而化感物质能干扰种子萌发过程中激素以及ROS的平衡, 从而影响种子萌发。因此, 深入探讨化感物质干扰激素和ROS的分子机理, 以及在这个过程中ROS如何参与到激素的调节通路中, 将是非常有意义的。

最后, 现在化感作用研究多集中在理论研究阶段, 如何将化感作用研究成果应用于实践, 是目前亟待解决的问题之一。我们现在已经知道很多植物具有化感作用, 但是能应用到实际生产中的成果很少。因此, 要进一步思考如何在现有研究成果的基础上, 探讨合理的农作物间套作搭配方式, 开发新型绿色除草剂, 使化感作用真正促进农业的发展。

| [1] | 郭兰萍, 黄璐琦, 蒋有绪, 等. 药用植物栽培种植中的土壤环境恶化及防治策略[J]. 中国中药杂志 , 2006, 31 (9) : 714–717. Guo L P, Huang L Q, Jiang Y X, et al. Soil deterioration dur-ing cultivation of medicinal plants and ways to prevent it[J]. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica , 2006, 31 (9) : 714–717. |

| [2] | Farooq M, Jabran K, Cheema Z A, et al. The role of allelopa-thy in agricultural pest management[J]. Pest Management Science , 2011, 67 (5) : 493–506. DOI:10.1002/ps.v67.5 |

| [3] | Weir T L, Park S W, Vivanco J M. Biochemical and physio-logical mechanisms mediated by allelochemicals[J]. Current Opinion in Plant Biology , 2004, 7 (4) : 472–479. DOI:10.1016/j.pbi.2004.05.007 |

| [4] | Callaway R M, Pennings S C, Richards C L. Phenotypic plasticity and interactions among plants[J]. Ecology , 2003, 84 (5) : 1115–1128. DOI:10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[1115:PPAIAP]2.0.CO;2 |

| [5] | 黄乔乔, 沈奕德, 李晓霞, 等. 外来入侵植物在中国的分布及入侵能力研究进展[J]. 生态环境学报 , 2012, 21 (5) : 977–985. Huang Q Q, Shen Y D, Li X X, et al. Research progress on the distribution and invasiveness of alien invasive plants in China[J]. Ecology and Environmental Sciences , 2012, 21 (5) : 977–985. |

| [6] | Chu C J, Mortimer P, Wang H C, et al. Allelopathic effects of Eucalyptus on native and introduced tree species[J]. Forest Ecology and Management , 2014, 323 : 79–84. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2014.03.004 |

| [7] | Bughio F A, Mangrio S M, Abro S A, et al. Physio-morpho-logical responses of native Acacia nilotica to eucalyptus al-lelopathy[J]. Pakistan Journal of Botany , 2013, 45 (S1) : 97–105. |

| [8] | Liu X B, Herbert S J. Fifteen years of research examining cultivation of continuous soybean in northeast China:A re-view[J]. Field Crops Research , 2002, 79 (1) : 1–7. DOI:10.1016/S0378-4290(02)00042-4 |

| [9] | 杜英君, 靳月华. 连作大豆植株化感作用的模拟研究[J]. 应用生态学报 , 1999, 10 (2) : 209–212. Du Y J, Jin Y H. Simulations of allelopathy in continuous cropping of soybean[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology , 1999, 10 (2) : 209–212. |

| [10] | Yuan Y G, Wang B, Zhang S S, et al. Enhanced allelopathy and competitive ability of invasive plant Solidago canadensis in its introduced range[J]. Journal of Plant Ecology , 2013, 6 (3) : 253–263. DOI:10.1093/jpe/rts033 |

| [11] | Barrero J M, Downie A B, Xu Q, et al. A role for barley CRYPTOCHROME1 in light regulation of grain dormancy and germination[J]. The Plant Cell , 2014, 26 (3) : 1094–1104. DOI:10.1105/tpc.113.121830 |

| [12] | Ishibashi Y, Koda Y, Zheng S H, et al. Regulation of soybean seed germination through ethylene production in response to reactive oxygen species[J]. Annals of Botany , 2012, 111 (1) : 95–102. |

| [13] | El-Maarouf-Bouteau H, Sajjad Y, Bazin J, et al. Reactive ox-ygen species, abscisic acid and ethylene interact to regulate sunflower seed germination[J]. Plant, Cell & Environment , 2015, 38 (2) : 364–374. |

| [14] | 帅海威, 孟永杰, 罗晓峰, 等. 生长素调控种子的休眠与萌发[J]. 遗传 , 2016, 38 (4) : 314–322. Shuai H W, Meng Y J, Luo X F, et al. The roles of auxin in seed dormancy and germination[J]. Hereditas , 2016, 38 (4) : 314–322. |

| [15] | Chon S U, Jang H G, Kim D K, et al. Allelopathic potential in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) plants[J]. Scientia Horticulturae , 2005, 106 (3) : 309–317. DOI:10.1016/j.scienta.2005.04.005 |

| [16] | 倪利晓, 陈世金, 任高翔, 等. 陆生植物化感作用的抑藻研究进展[J]. 生态环境学报 , 2011, 20 (6/7) : 1176–1182. Ni L X, Chen S J, Ren G X, et al. Advance research on the allelopathy of terrestrial plants in inhibition of algae[J]. Ecology and Environmental Sciences , 2011, 20 (6/7) : 1176–1182. |

| [17] | Rice E L. Allelopathy-An update[J]. The Botanical Review , 1979, 45 (1) : 15–109. DOI:10.1007/BF02869951 |

| [18] | Rice E L. Allelopathy[M]. New York: Academic Press, 1984 : 1 -267. |

| [19] | Dias L S, Pereira I P, Dias A S. Allelopathy, seed germination, weed control and bioassay methods[J]. Allelopathy Journal , 2016, 37 (1) : 31–40. |

| [20] | Zhang D J, Zhang J, Yang W Q, et al. Potential allelopathic effect of Eucalyptus grandis across a range of plantation ag-es[J]. Ecological Research , 2010, 25 (1) : 13–23. DOI:10.1007/s11284-009-0627-0 |

| [21] | Oracz K, Bailly C, Gniazdowska A, et al. Induction of oxida-tive stress by sunflower phytotoxins in germinating mustard seeds[J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology , 2007, 33 (2) : 251–264. DOI:10.1007/s10886-006-9222-9 |

| [22] | Bauer J T, Shannon S M, Stoops R E, et al. Context depend-ency of the allelopathic effects of Lonicera maackii on seed germination[J]. Plant Ecology , 2012, 213 (12) : 1907–1916. DOI:10.1007/s11258-012-0036-2 |

| [23] | Valera-Burgos J, Díaz-barradas M C, Zunzunegui M. Effects of Pinus pinea litter on seed germination and seedling per-formance of three Mediterranean shrub species[J]. Plant Growth Regulation , 2012, 66 (3) : 285–292. DOI:10.1007/s10725-011-9652-4 |

| [24] | Wang C Y, Xiao H G, Zhao L L, et al. The allelopathic effects of invasive plant Solidago canadensis on seed germination and growth of Lactuca sativa enhanced by different types of acid deposition[J]. Ecotoxicology , 2016, 25 (3) : 555–562. DOI:10.1007/s10646-016-1614-1 |

| [25] | Yu H Y, Hongbo L, Guoming S, et al. Effects of allelochemi-cals from tobacco root exudates on seed germination and seedling growth of tobacco[J]. Allelopathy Journal , 2014, 33 (1) : 107–120. |

| [26] | Wang Y Y, Wu F Z, Liu S W. Allelopathic effects of root ex-udates from wheat, oat and soybean on seed germination and growth of cucumber[J]. Allelopathy Journal , 2009, 24 (1) : 103–112. |

| [27] | Dorning M, Cipollini D. Leaf and root extracts of the invasive shrub, Lonicera maackii, inhibit seed germination of three herbs with no autotoxic effects[J]. Plant Ecology , 2006, 184 (2) : 287–296. DOI:10.1007/s11258-005-9073-4 |

| [28] | Butcko V M, Jensen R J. Evidence of tissue-specific alle-lopathic activity in Euthamia graminifolia and Solidago canadensis (Asteraceae)[J]. The American Midland Naturalist , 2002, 148 (2) : 253–262. DOI:10.1674/0003-0031(2002)148[0253:EOTSAA]2.0.CO;2 |

| [29] | Han C M, Pan K W, Wu N, et al. Allelopathic effect of ginger on seed germination and seedling growth of soybean and chive[J]. Scientia Horticulturae , 2008, 116 (3) : 330–336. DOI:10.1016/j.scienta.2008.01.005 |

| [30] | Mcewan R W, Arthur-Paratley L G, Rieske L K, et al. A mul-ti-assay comparison of seed germination inhibition by Lonicera maackii and co-occurring native shrubs[J]. Flora-Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants , 2010, 205 (7) : 475–483. DOI:10.1016/j.flora.2009.12.031 |

| [31] | Yang M, Zhang X D, Xu Y G, et al. Autotoxic ginsenosides in the rhizosphere contribute to the replant failure of Panax notoginseng[J]. PLoS One , 2015, 10 (2) : e0118555. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0118555 |

| [32] | Asaduzzaman M, Asao T. Autotoxicity in beans and their al-lelochemicals[J]. Scientia Horticulturae , 2012, 134 : 26–31. DOI:10.1016/j.scienta.2011.11.035 |

| [33] | Li Z F, Yang Y Q, Xie D F, et al. Identification of autotoxic compounds in fibrous roots of Rehmannia (Rehmannia glutinosa Libosch.)[J]. PLoS One , 2012, 7 (1) : e28806. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0028806 |

| [34] | Zhang W, Ma Y Q, Wang Z, et al. Some soybean cultivars have ability to induce germination of sunflower broomrape[J]. PLoS One , 2013, 8 (3) : e59715. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0059715 |

| [35] | Ma Y Q, Jia J N, Yu A, et al. Potential of some hybrid maize lines to induce germination of sunflower broomrape[J]. Crop Science , 2013, 53 (1) : 260–270. DOI:10.2135/cropsci2012.03.0197 |

| [36] | Lins R D, Colquhoun J B, Mallory-Smith C A. Investigation of wheat as a trap crop for control of Orobanche minor[J]. Weed Research , 2006, 46 (4) : 313–318. DOI:10.1111/wre.2006.46.issue-4 |

| [37] | 王钟, 马永清, 贾锦楠, 等. 马铃薯对瓜列当种子萌发的化感作用研究[J]. 中国生态农业学报 , 2013, 21 (3) : 333–339. Wang Z, Ma Y Q, Jia J N, et al. Allelopathic effect of potato on Orabanche aegyptiaca Pers. seed germination[J]. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture , 2013, 21 (3) : 333–339. |

| [38] | 余蕊, 马永清. 大麻对瓜列当和向日葵列当种子萌发诱导作用研究[J]. 中国农业大学学报 , 2014, 19 (4) : 38–46. Yu R, Ma Y Q. Melon broomrape and sunflower broomrape seeds germination induced by hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) plants[J]. Journal of China Agricultural University , 2014, 19 (4) : 38–46. |

| [39] | 郎明, 马永清, 董淑琦, 等. 苗期棉花对向日葵列当种子萌发诱导作用初探[J]. 生态环境学报 , 2011, 20 (1) : 79–83. Lang M, Ma Y Q, Dong S Q, et al. Allelopathic effect of cot-ton in seedling stage on sunflower broomrape[J]. Ecology and Environmental Sciences , 2011, 20 (1) : 79–83. |

| [40] | Rejila S, Vijayakumar N. Allelopathic effect of Jatropha cur-cas on selected intercropping plants (green chilli and sesa-me)[J]. Journal of Phytology , 2011, 3 (5) : 1–3. |

| [41] | Weitbrecht K, Müller K, Leubner-Metzger G. First off the mark:Early seed germination[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany , 2011, 62 (10) : 3289–3309. DOI:10.1093/jxb/err030 |

| [42] | Turk M A, Tawaha A M. Allelopathic effect of black mustard (Brassica nigra L.) on germination and growth of wild oat (Avena fatua L.)[J]. Crop Protection , 2003, 22 (4) : 673–677. DOI:10.1016/S0261-2194(02)00241-7 |

| [43] | Nishida N, Tamotsu S, Nagata N, et al. Allelopathic effects of volatile monoterpenoids produced by Salvia leucophylla:Inhibition of cell proliferation and DNA synthesis in the root apical meristem of Brassica campestris seedlings[J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology , 2005, 31 (5) : 1187–1203. DOI:10.1007/s10886-005-4256-y |

| [44] | 胡琬君, 马丹炜, 王亚男, 等. 土荆芥挥发油对蚕豆根尖细胞的化感潜力[J]. 生态学报 , 2011, 31 (13) : 3684–3690. Hu W J, Ma D W, Wang Y N, et al. Allelopathic potential of volatile oil from Chenopodium ambrosioides L. on root tip cells of Vicia faba[J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica , 2011, 31 (13) : 3684–3690. |

| [45] | Cruz-Ortega R, Anaya A L, Hernández-Bautista B E, et al. Effects of allelochemical stress produced by Sicyos deppei on seedling root ultrastructure of Phaseolus vulgaris and Cucurbita ficifolia[J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology , 1998, 24 (12) : 2039–2057. DOI:10.1023/A:1020733625727 |

| [46] | Xiong L M, Schumaker K S, Zhu J K. Cell signaling during cold, drought, and salt stress[J]. The Plant Cell , 2002, 14 (S1) : S165–S183. |

| [47] | Miller G, Suzuki N, Ciftci-Yilmaz S, et al. Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signalling during drought and salinity stresses[J]. Plant, Cell & Environment , 2010, 33 (4) : 453–467. |

| [48] | Sharma P, Jha A B, Dubey R S, et al. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions[J]. Journal of Botany , 2012, 2012 : 217037. |

| [49] | Chen C M, Letnik I, Hacham Y, et al. ASCORBATE PEROXIDASE6 protects Arabidopsis desiccating and germi-nating seeds from stress and mediates cross talk between re-active oxygen species, abscisic acid, and auxin[J]. Plant Physiology , 2014, 166 (1) : 370–383. DOI:10.1104/pp.114.245324 |

| [50] | Pergo É M, Ishii-Iwamoto E L. Changes in energy metabolism and antioxidant defense systems during seed germination of the weed species Ipomoea triloba L. and the responses to allelochemicals[J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology , 2011, 37 (5) : 500–513. DOI:10.1007/s10886-011-9945-0 |

| [51] | Abenavoli M R, Cacco G, Sorgonà A, et al. The inhibitory effects of coumarin on the germination of durum wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. durum, cv. Simeto) seeds[J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology , 2006, 32 (2) : 489–506. DOI:10.1007/s10886-005-9011-x |

| [52] | Oracz K, Voegele A, Tarkowsk D, et al. Myrigalone A inhibits Lepidium sativum seed germination by interference with gibberellin metabolism and apoplastic superoxide production required for embryo extension growth and endosperm rupture[J]. Plant and Cell Physiology , 2012, 53 (1) : 81–95. DOI:10.1093/pcp/pcr124 |

| [53] | Voegele A, Graeber K, Oracz K, et al. Embryo growth, testa permeability, and endosperm weakening are major targets for the environmentally regulated inhibition of Lepidium sativum seed germination by myrigalone A[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany , 2012, 63 (14) : 5337–5350. DOI:10.1093/jxb/ers197 |

| [54] | Kato-Noguchi H, Macías F A. Inhibition of germination and α-amylase induction by 6-methoxy-2-benzoxazolinone in twelve plant species[J]. Biologia Plantarum , 2008, 52 (2) : 351–354. DOI:10.1007/s10535-008-0072-x |

| [55] | Kato-Noguchi H, Macías F A. Effects of 6-methoxy-2-benzoxazolinone on the germination and α-amylase activity in lettuce seeds[J]. Journal of Plant Physiology , 2005, 162 (12) : 1304–1307. DOI:10.1016/j.jplph.2005.03.013 |

| [56] | Kupidłowska E, Gniazdowska A, Stępień J, et al. Impact of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) extracts upon reserve mobilization and energy metabolism in germinating mustard (Sinapis alba L.) seeds[J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology , 2006, 32 (12) : 2569–2583. DOI:10.1007/s10886-006-9183-z |

| [57] | Miransari M, Smith D L. Plant hormones and seed germina-tion[J]. Environmental and Experimental Botany , 2014, 99 : 110–121. DOI:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2013.11.005 |

| [58] | Shu K, Meng Y J, Shuai H W, et al. Dormancy and germina-tion:How does the crop seed decide?[J]. Plant Biology , 2015, 17 (6) : 1104–1112. DOI:10.1111/plb.2015.17.issue-6 |

| [59] | Shu K, Chen Q, Wu Y R, et al. ABI4 mediates antagonistic effects of abscisic acid and gibberellins at transcript and protein levels[J]. The Plant Journal , 2015, 85 (3) : 348–361. |

| [60] | Linkies A, Leubner-Metzger G. Beyond gibberellins and ab-scisic acid:How ethylene and jasmonates control seed ger-mination[J]. Plant Cell Reports , 2012, 31 (2) : 253–270. DOI:10.1007/s00299-011-1180-1 |

| [61] | Shu K, Zhang H W, Wang S F, et al. ABI4 regulates primary seed dormancy by regulating the biogenesis of abscisic acid and gibberellins in Arabidopsis[J]. PLoS Genetics , 2013, 9 (6) : e1003577. DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003577 |

| [62] | Holdsworth M J, Bentsink L, Soppe W J J. Molecular net-works regulating Arabidopsis seed maturation, after-ripening, dormancy and germination[J]. New Phytologist , 2008, 179 (1) : 33–54. DOI:10.1111/nph.2008.179.issue-1 |

| [63] | Finkelstein R, Reeves W, Ariizumi T, et al. Molecular aspects of seed dormancy[J]. Annual Review of Plant Biology , 2008, 59 (1) : 387–415. DOI:10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092740 |

| [64] | Skene K R, Sprent J I, Raven J A, et al. Myrica gale L.[J]. Journal of Ecology , 2000, 88 (6) : 1079–1094. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2745.2000.00522.x |

| [65] | Popovici J, Bertrand C, Jacquemoud D, et al. An allelochem-ical from Myrica gale with strong phytotoxic activity against highly invasive Fallopia x bohemica taxa[J]. Molecules , 2011, 16 (3) : 2323–2333. |

| [66] | Gniazdowska A, Oraczr K, Bogatek R. Phytotoxic effects of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) leaf extracts on germinating mustard (Sinapis alba L.) seeds[J]. Allelopathy Journal , 2007, 19 (1) : 215–226. |

| [67] | Zhu Y, Li Q X. Movement of bromacil and hexazinone in soils of Hawaiian pineapple fields[J]. Chemosphere , 2002, 49 (6) : 669–674. DOI:10.1016/S0045-6535(02)00392-2 |

| [68] | Roeleveld N, Bretveld R. The impact of pesticides on male fertility[J]. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology , 2008, 20 (3) : 229–233. DOI:10.1097/GCO.0b013e3282fcc334 |

| [69] | Dayan F E, Cantrell C L, Duke S O. Natural products in crop protection[J]. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry , 2009, 17 (12) : 4022–4034. |

| [70] | Schulz M, Marocco A, Tabaglio V, et al. Benzoxazinoids in rye allelopathy-from discovery to application in sustainable weed control and organic farming[J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology , 2013, 39 (2) : 154–174. DOI:10.1007/s10886-013-0235-x |

| [71] | Kato-Noguchi H, Peters R J. The role of momilactones in rice allelopathy[J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology , 2013, 39 (2) : 175–185. DOI:10.1007/s10886-013-0236-9 |

| [72] | Weston L A, Alsaadawi I S, Baerson S R. Sorghum allelopa-thy-From ecosystem to molecule[J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology , 2013, 39 (2) : 142–153. DOI:10.1007/s10886-013-0245-8 |

| [73] | Bogatek R, Gniazdowska A, Zakrzewska W, et al. Allelopa-thic effects of sunflower extracts on mustard seed germination and seedling growth[J]. Biologia Plantarum , 2006, 50 (1) : 156–158. DOI:10.1007/s10535-005-0094-6 |

| [74] | Fragasso M, Iannucci A, Papa R. Durum wheat and allelopa-thy:Toward wheat breeding for natural weed management[J]. Frontiers Plant in Science , 2013, 4 : 375. |

| [75] | 王建花, 陈婷, 林文雄. 植物化感作用类型及其在农业中的应用[J]. 中国生态农业学报 , 2013, 21 (10) : 1173–1183. Wang J H, Chen T, Lin W X. Plant allelopathy types and their application in agriculture[J]. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture , 2013, 21 (10) : 1173–1183. DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1011.2013.01173 |

| [76] | Vyvyan J R. Allelochemicals as leads for new herbicides and agrochemicals[J]. Tetrahedron , 2002, 58 (9) : 1631–1646. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(02)00052-2 |

| [77] | Jabran K, Mahajan G, Sardana V, et al. Allelopathy for weed control in agricultural systems[J]. Crop Protection , 2015, 72 : 57–65. DOI:10.1016/j.cropro.2015.03.004 |

| [78] | Macías F A, Molinillo J M, Galindo J C G, et al. The use of allelopathic studies in the search for natural herbicides[J]. Journal of Crop Production , 2001, 4 (2) : 237–255. DOI:10.1300/J144v04n02_08 |

| [79] | Khanh T D, Chung M I, Xuan T D, et al. The exploitation of crop allelopathy in sustainable agricultural production[J]. Zeitschrift fur Acker-und Pflanzenbau , 2005, 191 (3) : 172–184. DOI:10.1111/j.1439-037X.2005.00172.x |

| [80] | Dilipkumar M, Chuah T S. Is combination ratio an important factor to determine synergistic activity of allelopathic crop extract and herbicide?[J]. International Journal of Agriculture & Biology , 2013, 15 (2) : 259–265. |

| [81] | Blackshaw R E, Moyer J R, Doram R C, et al. Yellow sweet-clover, green manure, and its residues effectively suppress weeds during fallow[J]. Weed Science , 2001, 49 (3) : 406–413. DOI:10.1614/0043-1745(2001)049[0406:YSGMAI]2.0.CO;2 |

| [82] | Moyer J R, Blackshaw R E, Huang H C. Effect of sweetclover cultivars and management practices on following weed infestations and wheat yield[J]. Canadian Journal of Plant Science , 2007, 87 (4) : 973–983. DOI:10.4141/CJPS06054 |

| [83] | Tesio F, Vidotto F, Ferrero A. Allelopathic persistence of He-lianthus tuberosus L. residues in the soil[J]. Scientia Horti-culturae , 2012, 135 : 98–105. DOI:10.1016/j.scienta.2011.12.008 |

| [84] | 鞠瑞亭, 李慧, 石正人, 等. 近十年中国生物入侵研究进展[J]. 生物多样性 , 2012, 20 (5) : 581–611. Ju R T, Li H, Shi Z R, et al. Progress of biological invasions research in China over the last decade[J]. Biodiversity Sci-ence , 2012, 20 (5) : 581–611. |

| [85] | Schittko C, Wurst S. Above-and belowground effects of plant-soil feedback from exotic Solidago canadensison native Tanacetum vulgare[J]. Biological Invasions , 2014, 16 (7) : 1465–1479. DOI:10.1007/s10530-013-0584-y |

| [86] | Shen S C, Xu G F, Clements D R, et al. Suppression of the invasive plant mile-a-minute (Mikania micrantha) by local crop sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) by means of higher growth rate and competition for soil nutrients[J]. BMC Ecol-ogy , 2015, 15 : 1. DOI:10.1186/s12898-014-0033-5 |

| [87] | Hodgins K A, Lai Z, Nurkowski K, et al. The molecular basis of invasiveness:Differences in gene expression of native and introduced common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) in stressful and benign environments[J]. Molecular Ecology , 2013, 22 (9) : 2496–2510. DOI:10.1111/mec.12179 |

| [88] | 张敏, 付冬梅, 陈华保, 等. 紫茎泽兰叶片对小麦、油菜幼苗的化感作用及化感机制的初步研究[J]. 浙江大学学报:农业与生命科学版 , 2010, 36 (5) : 547–553. Zhang M, Fu D M, Chen H B, et al. Preliminary study on allelopathic effects and mechanism of Eupatorium ade-nophorum to wheat and rape seedlings[J]. Journal of Zhejiang University:Agriculture & Life Sciences , 2010, 36 (5) : 547–553. |

| [89] | Jarchow M E, Cook B J. Allelopathy as a mechanism for the invasion of Typha angustifolia[J]. Plant Ecology , 2009, 204 (1) : 113–124. DOI:10.1007/s11258-009-9573-8 |

| [90] | Greer M J, Wilson G W, Hickman K R, et al. Experimental evidence that invasive grasses use allelopathic biochemicals as a potential mechanism for invasion:Chemical warfare in nature[J]. Plant and Soil , 2014, 385 (1/2) : 165–179. |

| [91] | 万欢欢, 刘万学, 万方浩. 紫茎泽兰叶片凋落物对入侵地4种草本植物的化感作用[J]. 中国生态农业学报 , 2011, 19 (1) : 130–134. Wan H H, Liu W X, Wan F H. Allelopathic effect of Ageratina adenophora (Spreng.) leaf litter on four herbaceous plants in invaded regions[J]. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture , 2011, 19 (1) : 130–134. DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1011.2011.00130 |

| [92] | 类延宝, 肖海峰, 冯玉龙. 外来植物入侵对生物多样性的影响及本地生物的进化响应[J]. 生物多样性 , 2010, 18 (6) : 622–630. Lei Y B, Xiao H F, Feng Y L. Impacts of alien plant invasions on biodiversity and evolutionary responses of native species[J]. Biodiversity Science , 2010, 18 (6) : 622–630. DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1003.2010.622 |

| [93] | 彭少麟, 邵华. 化感作用的研究意义及发展前景[J]. 应用生态学报 , 2001, 12 (5) : 780–786. Peng S L, Shao H. Research significance and foreground of allelopathy[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology , 2001, 12 (5) : 780–786. |

| [94] | Singh H P, Batish D R, Kohli R K. Autotoxicity:Concept, organisms, and ecological significance[J]. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences , 1999, 18 (6) : 757–772. DOI:10.1080/07352689991309478 |

| [95] | Ruan X, Li ZH, Wang Q, et al. Autotoxicity and allelopathy of 3, 4-dihydroxyacetophenone isolated from Picea schrenkiana needles[J]. Molecules , 2011, 16 (10) : 8874–8893. |

| [96] | Chen L C, Wang S L, Wang P, et al. Autoinhibition and soil allelochemical (cyclic dipeptide) levels in replanted Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) plantations[J]. Plant and Soil , 2014, 374 (1/2) : 793–801. |

| [97] | Chon S U, Coutts J H, Nelson C J. Effects of light, growth media, and seedling orientation on bioassays of alfalfa auto-toxicity[J]. Agronomy Journal , 2000, 92 (4) : 715–720. DOI:10.2134/agronj2000.924715x |

| [98] | 张文明, 邱慧珍, 张春红, 等. 连作马铃薯不同生育期根系分泌物的成分检测及其自毒效应[J]. 中国生态农业学报 , 2015, 23 (2) : 215–224. Zhang W M, Qiu H Z, Zhang C H, et al. Identification and autotoxicity of root exudates of continuous cropping potato at different growth stages[J]. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture , 2015, 23 (2) : 215–224. |

| [99] | 李登武, 王冬梅, 姚文旭. 油松的自毒作用及其生态学意义[J]. 林业科学 , 2010, 46 (11) : 174–178. Li D W, Wang D M, Yao W X. Autotoxicity of Pinus tabu-laeformis and its ecology significance[J]. Scientia Silvae Sinicae , 2010, 46 (11) : 174–178. |

| [100] | 林思祖, 黄世国, 曹光球, 等. 杉木自毒作用的研究[J]. 应用生态学报 , 1999, 10 (6) : 661–664. Lin S Z, Huang S G, Cao G Q, et al. Autointoxication of Chi-nese fir[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology , 1999, 10 (6) : 661–664. |

| [101] | 马祥庆, 刘爱琴, 黄宝龙. 杉木人工林自毒作用研究[J]. 南京林业大学学报 , 2000, 24 (1) : 12–16. Ma X Q, Liu A Q, Huang B L. A study on self-poisoning ef-fects of Chinese fir plantation[J]. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University , 2000, 24 (1) : 12–16. |

| [102] | Wu H W, Pratley J, Lemerle D, et al. Autotoxicity of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) as determined by laboratory bioas-says[J]. Plant and Soil , 2007, 296 (1/2) : 85–93. |

| [103] | Mondal M F, Asaduzzaman M, Kobayashi Y, et al. Recovery from autotoxicity in strawberry by supplementation of amino acids[J]. Scientia Horticulturae , 2013, 164 : 137–144. DOI:10.1016/j.scienta.2013.09.019 |

| [104] | 张重义, 林文雄. 药用植物的化感自毒作用与连作障碍[J]. 中国生态农业学报 , 2009, 17 (1) : 189–196. Zhang C Y, Lin W X. Continuous cropping obstacle and allelopathic autotoxicity of medicinal plants[J]. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture , 2009, 17 (1) : 189–196. DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1011.2009.00189 |

2017, Vol. 25

2017, Vol. 25