自然环境中的含氮化合物约1/2来自生物固氮, 1/2来自人类活动, 主要是肥料的生产和石油的消耗[1]。大量微生物能将空气中的N2还原成铵态氮, 并与植物[主要是豆科(Leguminosae)植物]建立共生关系, 其中, 根瘤菌能与一百多种农业作物共生固氮[1]。据统计, 在全球范围内, 根瘤菌与豆科作物共生固定的氮素每年大约有2亿t[2]。豆科作物是重要的粮食作物和经济作物, 占世界主要作物产量的25%[1]。豆科作物根瘤固定的氮素会残留在土壤中为非豆科作物提供氮源[3], 因此被广泛应用于轮作和间套作系统, 具有明显的生态效益和经济效益。

共生关系的建立始于豆科作物与根瘤菌的分子信号交流。豆科植物缺氮时植株根系会分泌一类特殊的类黄酮物质, 它是一大类具有C6-C3-C6结构基本骨架的低分子量多酚类物质的总称。根瘤菌感知类黄酮信号后会生成结瘤因子(nod factor, NF), 结瘤因子是一类专一性脂壳寡糖信号(lipochitooligosacc harides, LCOs)[4], 它能使根毛变形卷曲并产生持续的胞内Ca2+振荡, 引发一系列信号级联放大反应, 激活下游转录调节子的转录, 其中包括钙离子/钙调素蛋白激酶CCaMK (calcium and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase)[5-6]、NSP1 (nodulation signaling pathway 1)[7]、NSP2 (nodulation signaling pathway 2)[8]、ERN (Ets2 repressor factor required for nodulation)[9]和NIN (nodule inception)[10-11]。而这些转录调节子能激活早期结瘤基因(early nodulation genes, ENODs)的表达[12], 诱发根瘤形成。根瘤中的固氮根瘤菌能与宿主植株进行有效的代谢物交换, 根瘤菌将空气中的氮气转换为氨为宿主提供氮源, 而宿主保护共生根瘤菌不受环境威胁的同时为其提供有机碳[2]。

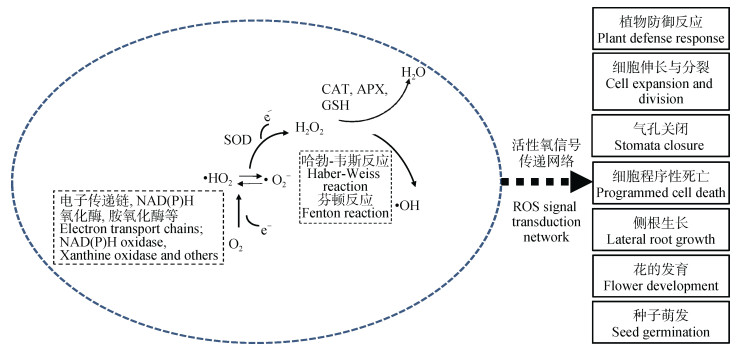

活性氧(reactive oxygen species, ROS)是氧分子(O2)逐步还原所产生的一类具有高反应活性的代谢产物。氧分子单电子还原形成超氧阴离子(·O2-)和过氧羟自由基(·HO2), 第2次单电子还原会形成过氧化氢(H2O2), 第3次单电子还原则产生羟自由基(·OH), 而·OH的再次还原形成水分子(H2O)(图 1)。在植物体内, ROS主要在叶绿体、线粒体和过氧化物酶体中产生, 是植株有氧代谢的副产物。正常生理状态下, 植物细胞体内产生的ROS水平较低。ROS的化学不稳定性使其在生物体中发挥多方面功能, 特别是植物与微生物的互作过程中[13-14]。早年研究发现植株在受到病原体感染时会使宿主产生一种特殊的信号——氧化爆发, 即短时间内大量的ROS产生以抵御病原体入侵。这些ROS不仅具有直接的抗菌作用, 而且能影响防御基因的表达、过敏反应的激活、细胞壁蛋白的交联和植保素的产生等[15]。同时, 植物能维持适当的ROS浓度使其作为第二信使介导植株生长和对外界环境的响应, 如细胞伸长与分裂[16-18]、气孔关闭、种子萌发、细胞程序性死亡[19-20]以及侧根的生长与花的发育[21]。研究发现根瘤菌在浸染豆科作物时同样会伴随ROS水平的变化。这种变化区别于病原体入侵, 而是作为一种重要的信号物质促使结瘤发生。

|

图 1 活性氧的产生和信号调控 Fig. 1 Generation and signal transduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) |

豆科植物感知NFs信号后会使根毛卷曲, 包裹根瘤菌, 根瘤菌穿过根毛形成浸染线逐步进入根皮层, 最终形成根瘤。该过程包含了一系列复杂的信号转导机制: Ca2+内流与Ca2+振荡、ROS的产生、细胞质的烷基化以及结瘤基因的表达[22]。NF处理数秒后的菜豆(Phaseolus vulgaris)根毛细胞尖端能检测到短暂升高的ROS, 且不同于真菌诱导子、ATP、H2O2以及UV处理下的ROS水平。因此, NF能诱导ROS的产生, 且该ROS具有NF诱导的特异性[23]。突变菌nodD1ABC不能产生NF, 当它与蒺藜苜蓿(Medicago truncatula)接种时, 检测不到ROS的变化, 说明ROS的产生可能发生在NF信号感知的下游[24]。Breakspear等[25]发现NF能激活结瘤诱导的过氧化物酶基因(rhizobially induced peroxidases, RIPs), 这些基因的表达可能与ROS的产生有关。

细胞质膜NADPH氧化酶(respiratory burst oxidase homologue, RBOHs)是植物与病原体互作过程中氧化爆发的主要来源[26], 也是共生过程中ROS产生的重要途径[27]。NF受体突变的苜蓿(Medicago sativat)植株nfp在NF处理下不能抑制过氧化氢的外流率, 而将野生型苜蓿用NF预处理1 h后, 添加DPI(NADPH氧化酶活性抑制剂)会使过氧化氢外流率较对照减少20%, 可以推测NADPH氧化酶可能参与NF诱导下的ROS的产生[28]。无活性的NF处理后的苜蓿检测不到ROS的变化, 说明根毛中RBOHs依赖的ROS水平变化需要特殊的NF的激活[29]。然而, 这种NF的诱导并非持续的, 一段时间后NF会抑制H2O2的产生[30-31]。NF的这种双重作用可能在根瘤菌与豆科作物的共生信号中扮演着重要角色。

2 ROS参与浸染线的形成和根瘤发育植株受到病原侵害时会迅速做出过敏反应(hypersensitive response, HR)。HR主要表现为浸染点的局部细胞死亡, 以阻碍细菌的进一步侵入, 同时会诱导系统防御抵抗烈性病原体。其早期特征是在短时间内产生大量的ROS[32]。研究发现根瘤菌浸染豆科植物时会发生过敏反应, 利用NBT着色法观察到苜蓿浸染线和年幼根瘤及成熟根瘤的浸染细胞中均有大量的ROS产生, 并使浸染点附近的根毛细胞迅速死亡[33-34]。而ROS的产生以及特定细胞的死亡与浸染口的形成密切相关[35]。根毛生长与浸染线的伸长具有相似性, 诸如浸染口丝状激动蛋白的累积和浸染线生长顶端分泌小泡的沉淀[36], 而ROS参与了浸染线延伸过程中细胞壁的重建[37]。H2O2能通过聚合细胞壁中的酚类物质来增加细胞壁硬度, 而氢氧自由基则通过裂解细胞壁聚合物增加细胞壁松弛程度[38]。Rubio等[39]在浸染线基质、外壁周围以及皮层细胞间隙中检测到大量H2O2, 可能与浸染线和细胞壁的形成有关。浸染线的形成是通过一种植物基质糖蛋白(plant matrix glycoprotein, MGP)的交联作用, 它主要存在于植物组织的胞外基质和浸染线的内腔, 而MGP的不溶性会受到H2O2的调节[40]。MtAblL能编码一种ABL类似蛋白, 这种蛋白参与了肌动蛋白微丝的成核和延长过程, 与根瘤菌的浸染密切相关, 而H2O2能调节MtAblL的表达[41]。

NADPH氧化酶是产生ROS的主要酶类。NADPH氧化酶抑制剂DPI处理蒺藜苜蓿根系会抑制根毛的卷曲和浸染线的形成[42]。NADPH氧化酶基因Rbohs近年来被发现存在于豆科植物的基因库中, 利用RNAi敲除菜豆中的NADPH氧化酶基因PvRbohB后, ROS产生明显减少且结瘤受到抑制[43]。而PvRbohB过表达的菜豆根系能促进根瘤菌的浸染, 增加根瘤数量[44]。Jamet等[45]利用H2O2稳态缺陷菌接种苜蓿时, 根瘤菌过氧化物酶的过量表达会减少浸染线中的H2O2浓度, 浸染线的形成受到影响。在拟南芥(Arabidopsis thaliana)中发现了一种膜联蛋白(AtAnn1), 它能调节RBOH来源的ROS刺激下Ca2+的内流[46-47]。Carrasco- Castilla等[48]发现菜豆PvAnn1-RNAi转基因根系中, 根瘤原基中ROS的产生受阻, NIN、ENOD2和PvRbohB的转录水平均下调, 导致浸染线的形成和延伸受到影响, 根瘤发育受到限制。因此, 植株可能利用PvAnn1调节ROS水平来控制浸染线的延伸及结瘤信号。根瘤中的一种特异性NCR多肽能控制类菌体的分裂过程[49]。研究发现, 花生(Arachis hypogaea)根瘤中H2O2的增加会提高类菌体的密度, ROS可能通过调节NCR的氧化还原状态来控制类菌体的分裂[50]。TOR蛋白参与了ROS信号的感知和信号传递[51], 菜豆的TOR-RNAi突变根系中, Rboh基因的转录水平下调, 且ROS水平下降, ROS相关结瘤基因RIP1转录显著下降, 浸染线数量明显降低, 且浸染受阻, 根瘤中共生体和类菌体数量减少, 固氮有效性下降[52]。ROS能控制根系细胞的增殖和分化[16], 根瘤生长发育过程中, ROS可能参与了根瘤原基的分化, 但具体机制有待进一步研究。

ROS不仅在早期根瘤形成中发挥了重要作用, 而且在后期根瘤的固氮功能中至关重要[44]。侵染后生长6周左右的根瘤细胞中有H2O2的存在[34], 而NADPH氧化酶基因Rboh主要在不定型根瘤的分生区尖端进行表达, 且该基因的表达与固氮能力密切相关, Rboh基因表达量的下降会显著抑制固氮酶活性[27]。Rboh过表达突变株的ROS含量增加, 根瘤中有更丰富的共生微粒体, 每个浸染细胞中的类菌体数量更多, 聚-β-羟基丁酸盐的含量更高, 有效提高了固氮效率[44]。根瘤固氮需要植株为类菌体提供碳源, 蔗糖合成酶在碳代谢中发挥了重要作用, 而根瘤中的氧化还原环境会影响蔗糖合成酶在根瘤中的功能。此外, ROS可能还参与了根瘤后期的衰老。不定型根瘤的衰老区及侵染后生长10周左右的定型根瘤的共生微粒体周围能检测到大量H2O2的存在, 这些H2O2可能与根瘤衰老时引发的氧化胁迫有关[53]。

3 Ca2+与ROS协同调控根系结瘤Ca2+信号是植物对外界环境作出生理和细胞反应的核心调节子。Ca2+流信息的编码和传递主要通过Ca2+结合蛋白上的Ca2+响应启动元件来调节转录和磷酸化, 从而影响基因的表达和细胞生理[54]。Ca2+信号流是结瘤过程中一条重要的信号通路[37]。

Ca2+和ROS是植物顶端生长的重要因素, 例如花粉管的生长以及根毛的伸长[55-57]。同时, 纤维细胞的生长也受到Ca2+和ROS的调控[58-59]。NADPH氧化酶产生的ROS对Ca2+通道的激活可能是ROS介导信号途径的重要步骤, 是植物常见的信号链路[37, 60-61], 而拟南芥AnnAt1可能参与了ROS和细胞质Ca2+浓度驱动的信号以及ROS激活的Ca2+流[62]。ROS可以激活细胞质膜Ca2+通道, Ca2+内流通过正反馈调节激活NADPH氧化酶相关的RBOH蛋白[37, 63-64], 主要依赖RBOH蛋白的EF-手型结构域和N端区上游区域[65]。可以推测, Ca2+流能同时作用于ROS的上游和下游[60]。

高等植物在受到病菌侵害时会发生氧化迸发, 该反应主要是由致病诱导子与特异受体的相互作用所致。诱导子与受体的结合会激活Ca2+通道产生Ca2+流从而调节NADPH氧化酶活性[28, 66]。豆科作物结瘤时, NF会引起豆科植物根毛细胞两种典型的离子情况变化, 一是Ca2+流, 二是Ca2+振荡[67]。研究发现, 影响Ca2+振荡的苜蓿突变体(dmi1、dmi2、dmi3、nsp1、nsp2和hcl)在受到NF处理时, ROS的产生会减少[28]。可以猜测Ca2可能与ROS存在某种联系。进一步研究发现, Ca2+变化的同时伴有ROS的产生。Ca2+与ROS在早期共生互作过程中可能发挥协同作用[23]。Morieri等[29]认为NF会激活NF受体诱导根瘤形成的两条途径, 第一条是Ca2+振荡, 其次是RBOH活性和Ca2+流, 后者与根瘤菌的浸染有关。尽管RBOH在这一过程中的激活机制尚不清楚, 但已有研究发现RBOH的N端能与Ca2+结合诱导ROS的产生[65, 68]。由于RBOH产生的ROS能促进Ca2+通道的打开[56], 可以猜测结瘤早期信号传递中, 二者可能存在某种反馈调节。Glyan’ko等[69]发现NADPH氧化酶的激活依赖Ca2+通道的打开, 而过多的Ca2+会抑制NADPH氧化酶的活性。在根毛细胞尖端, ROS在时空上的变化与Ca2+流相关联, NF信号感知后, 短暂的ROS响应可能会激活根毛尖端的Ca2+通道, Ca2+内流, 而Ca2+反过来会活化NAD(P)H氧化酶产生更多的ROS, 引发一系列信号传递[23](图 2)。

|

图 2 活性氧(ROS)与Ca2+在豆科作物结瘤信号传递中扮演的角色 Fig. 2 Roles of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and Ca2+ in nodulation signal transduction of Leguminosae crops LysM RLKs:受体激酶; RBOH:细胞质膜NADPH氧化酶。 LysM RLKs: receptor kinases; RBOH: respiratory burst oxidase homologue. |

ROS对根毛浸染有着重要作用, 但是持续升高的ROS水平对结瘤有不利影响[70]。在紫花苜蓿结瘤时不是所有的浸染线都会成功延伸至根瘤原基, 许多浸染线的形成会由于根皮层的过敏反应而中止[23]。外源施用ROS会阻碍NF诱导的根毛膨大和分枝[30]。因此, 有假设认为NF会激活第一次ROS的产生帮助结瘤, 而会抑制与防御反应相关的第二次ROS的产生[71]。NF通过调节植物的抗氧化机制和ROS生产系统[31], 抑制或清除ROS的产生来维持ROS在体内的稳态[23], 使根瘤菌能进入宿主而不会激发植株的防御反应[23]。

flg22是一种细菌鞭毛蛋白, 它能引发一系列防御反应, 如Ca2+内流、ROS的产生、丝裂原激活蛋白的活化以及基因的表达等。而将NF作用于非豆科作物拟南芥时, 它会抑制flg22诱导的ROS的产生[72]。NF处理菜豆根毛细胞时, ROS含量在1 min左右会达到最大值, 3 min后开始逐渐降低, 而H2O2和UV处理后其ROS的含量在3 min后仍然持续升高, 壳聚糖处理后在5min后急剧上升, 9 min达到最大值[30]。NF作用于蒺藜苜蓿根部时, 20~30 min后H2O2的流出会受到抑制[28], 且NADPH氧化酶同源物的转录表达减少。不难想象, ROS只有在适宜的时间与位置产生才能使根瘤菌顺利进入宿主而不引发过敏反应[23]。而蒺藜苜蓿对NF的初始响应是区别于防御反应下的氧化爆发。PGA是一类防御相关的氧化爆发诱导子, 研究发现, 同PGA处理比较, NF处理下的苜蓿略微加速了H2O2的外流, 且在20 min内发生逆转。可以认为, NF使植物过氧化氢外流率的减缓有助于根毛的卷曲和浸染所需的细胞壁生长的变化, 同时抑制了防御反应相关基因的表达[28]。植株也能通过调节体内抗氧化酶的代谢来控制氧化环境, 为共生发育提供合适的条件。Mu oz等[31]发现在花生接种后15~30 min, 其根系的过氧化氢酶(CAT)活性增加, 60 min后活性开始下降, 而过氧化酶(PX)在接种后30~60 min后增加, 240 min后开始下降。百脉根(Lotus corniculatus)根瘤中发现了两种谷胱甘肽过氧化酶(glutathione peroxidases, Gpxs)[73], 且在浸染区大量表达, NF通过激活和抑制相关的抗氧化物酶来合理控制氧化环境。

紫花苜蓿在结瘤共生时, 其浸染线中能检测到O2-和H2O2, 而在类菌体和根瘤菌中未能检测到ROS的存在, 表明根瘤菌存在一种高效的ROS清除机制。研究发现两种过氧化氢酶katB和katC在浸染过程中具有重要的作用, katB和katC突变菌不能正常结瘤[74], 根瘤菌从浸染线中释放后, 形成的类菌体迅速衰老。而过氧化氢酶编码基因katG及其转录激活子编码基因OxyR的突变菌也表现出根瘤数目的减少及固氮效率的降低[73]。细胞质超氧化物歧化酶(superoxide dismutase, SOD)的编码基因sodA的突变菌接种苜蓿后, 能被宿主正常识别, 且5 d后浸染线的数量与野生型植株无差异, 然而10 d后, 浸染线生长终止, 根瘤形成受阻。SOD的缺失使根瘤菌遭受氧化胁迫, 从而抑制了浸染线的形成[75]。花生与根瘤菌早期互作过程中, 根瘤菌中的过氧化酶(peroxidase, PX)参与调节宿主的氧化爆发免疫反应[50], 清除有害的ROS。

豆科作物通过控制ROS来调节早期结瘤相关的信号通路, 根瘤菌利用自身的抗氧化物酶改变氧化环境, 二者协调作用使浸染线正常形成, 最终诱导根瘤发生。

5 结论与展望豆科作物从根瘤菌浸染再到根瘤形成发育伴随着一系列复杂的信号传递。ROS同Ca2+一样在细胞信号转导中的作用不可小觑。它能作为一种信号物质间接调节早期结瘤过程, 通过ROS受体或Ca2+信号来激活相关基因的表达[41], 同时参与后期发育以及功能固氮(图 2)。根瘤菌与宿主的兼容性取决于防御反应的抑制程度[76], 而ROS的产生是植物常见的防御反应, 可能与结瘤特异性有重要联系。

除ROS外, 活性氮(RNS)是另一种参与植物生长发育及生物与非生物胁迫的活性物质[77-78]。共生结瘤过程中, NO在根瘤形成发育及功能固氮中同样发挥重要作用[79], 它能调节线粒体呼吸和碳氮代谢, 同时与ROS存在密切的联系[14, 71, 80], NO能通过调节NADPH氧化酶的活性来控制ROS的产生[81]。过氧化亚硝酸盐(ONOO-)是NO与O2-发生作用时的信号分子, 可能参与共生结瘤时二者的交互作用[82]。同时, Blanquet等[83]的研究证明了NO与O2-在根瘤中的直接联系。然而, 共生结瘤过程中ROS/NO交互作用类型还有待于继续挖掘。

非豆科作物由于不能正确识别结瘤因子而不能形成根瘤[84]。ROS的产生是植物与微生物早期的识别信号, 而在豆科结瘤过程中, ROS作用的靶基因和靶蛋白, ROS与NO的时空关系以及与防御反应的联系等尚不清楚。通过认识ROS在早期结瘤过程中的信号传递有助于进一步理解共生关系建立的特异性, 利用分子手段来控制共生关系, 扩大共生范围, 从而提高根瘤固氮的农业潜力。

| [1] |

JANCZAREK M, RACHWAŁ K, MARZEC A, et al. Signal molecules and cell-surface components involved in early stages of the legume-rhizobium interactions[J]. Applied Soil Ecology, 2015, 85: 94-113. |

| [2] |

HAAG A F, ARNOLD M F F, MYKA K K, et al. Molecular insights into bacteroid development during Rhizobium-legume symbiosis[J]. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2013, 37(3): 364-383. |

| [3] |

UDVARDI M, POOLE P S. Transport and metabolism in legume-rhizobia symbioses[J]. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 2013, 64: 781-805. |

| [4] |

HAYASHI S, GRESSHOFF P M, FERGUSON B J. Systemic signalling in legume nodulation: Nodule formation and its regulation[M]//BALUŠKA F. Long-Distance Systemic Signaling and Communication in Plants. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2013: 219-229

|

| [5] |

LÉVY J, BRES C, GEURTS R, et al. A putative Ca2+ and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase required for bacterial and fungal symbioses[J]. Science, 2004, 303(5662): 1361-1364. |

| [6] |

MITRA R M, GLEASON C A, EDWARDS A, et al. A Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase required for symbiotic nodule development:Gene identification by transcript-based cloning[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2004, 101(13): 4701-4705. |

| [7] |

SMIT P, RAEDTS J, PORTYANKO V, et al. NSP1 of the GRAS protein family is essential for Rhizobial nod factor-induced transcription[J]. Science, 2005, 308(5729): 1789-1791. DOI:10.1126/science.1111025 |

| [8] |

KALÓ P, GLEASON C, EDWARDS A, et al. Nodulation signaling in legumes requires NSP2, a member of the GRAS family of transcriptional regulators[J]. Science, 2005, 308(5729): 1786-1789. |

| [9] |

MIDDLETON P H, JAKAB J, PENMETSA R V, et al. An ERF transcription factor in Medicago truncatula that is essential for Nod factor signal transduction[J]. The Plant Cell, 2007, 19(4): 1221-1234. |

| [10] |

BORISOV A Y, MADSEN L H, TSYGANOV V E, et al. The Sym35 gene required for root nodule development in pea is an ortholog of Nin from Lotus japonicus[J]. Plant Physiology, 2003, 131(3): 1009-1017. |

| [11] |

SCHAUSER L, ROUSSIS A, STILLER J, et al. A plant regulator controlling development of symbiotic root nodules[J]. Nature, 1999, 402(6758): 191-195. |

| [12] |

FERGUSON B J, INDRASUMUNAR A, HAYASHI S, et al. Molecular analysis of legume nodule development and autoregulation[J]. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 2010, 52(1): 61-76. |

| [13] |

MITTLER R, VANDERAUWERA S, SUZUKI N, et al. ROS signaling:The new wave?[J]. Trends in Plant Science, 2011, 16(6): 300-309. |

| [14] |

PUPPO A, PAULY N, BOSCARI A, et al. Hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide:Key regulators of the legume-Rhizobium and mycorrhizal symbioses[J]. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 2013, 18(16): 2202-2219. |

| [15] |

O'BRIEN J A, DAUDI A, BUTT V S, et al. Reactive oxygen species and their role in plant defence and cell wall metabolism[J]. Planta, 2012, 236(3): 765-779. |

| [16] |

TSUKAGOSHI H, BUSCH W, BENFEY P N. Transcriptional regulation of ROS controls transition from proliferation to differentiation in the root[J]. Cell, 2010, 143(4): 606-616. |

| [17] |

LU D D, WANG T, PERSSON S, et al. Transcriptional control of ROS homeostasis by KUODA1 regulates cell expansion during leaf development[J]. Nature Communications, 2014, 5: 3767. |

| [18] |

SCHMIDT R, KUNKOWSKA A B, SCHIPPERS J H M. Role of reactive oxygen species during cell expansion in leaves[J]. Plant Physiology, 2016, 172(4): 2098-2106. |

| [19] |

YI J, MOON S, LEE Y S, et al. Defective tapetum cell death 1(DTC1) regulates ROS levels by binding to metallothionein during tapetum degeneration[J]. Plant Physiology, 2016, 170(3): 1611-1623. |

| [20] |

JIMÉNEZ-QUESADA M J, TRAVERSO J A, DE DIOS ALCHÉ J. NADPH oxidase-dependent superoxide production in plant reproductive tissues[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2016, 7: 359. |

| [21] |

MHAMDI A, VAN BREUSEGEM F. Reactive oxygen species in plant development[J]. Development, 2018, 145(15): dev164376. |

| [22] |

PELEG-GROSSMAN S, MELAMED-BOOK N, LEVINE A. ROS production during symbiotic infection suppresses pathogenesis-related gene expression[J]. Plant Signaling & Behavior, 2012, 7(3): 409-415. |

| [23] |

CÁRDENAS L, MARTÍNEZ A, SÁNCHEZ F, et al. Fast, transient and specific intracellular ROS changes in living root hair cells responding to Nod factors (NFs)[J]. The Plant Journal, 2008, 56(5): 802-813. |

| [24] |

RAMU S K, PENG H M, COOK D R. Nod factor induction of reactive oxygen species production is correlated with expression of the early nodulin gene rip1 in Medicago truncatula[J]. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 2002, 15(6): 522-528. |

| [25] |

BREAKSPEAR A, LIU C W, ROY S, et al. The root hair "Infectome" of Medicago truncatula uncovers changes in cell cycle genes and reveals a requirement for auxin signaling in rhizobial infection[J]. The Plant Cell, 2014, 26(12): 4680-4701. |

| [26] |

MARINO D, DUNAND C, PUPPO A, et al. A burst of plant NADPH oxidases[J]. Trends in Plant Science, 2012, 17(1): 9-15. |

| [27] |

MARINO D, ANDRIO E, DANCHIN E G J, et al. A Medicago truncatula NADPH oxidase is involved in symbiotic nodule functioning[J]. New Phytologist, 2011, 189(2): 580-592. |

| [28] |

SHAW S L, LONG S R. Nod factor inhibition of reactive oxygen efflux in a host legume[J]. Plant Physiology, 2003, 132(4): 2196-2204. |

| [29] |

MORIERI G, MARTINEZ E A, JARYNOWSKI A, et al. Host-specific Nod-factors associated with Medicago truncatula nodule infection differentially induce calcium influx and calcium spiking in root hairs[J]. New Phytologist, 2013, 200(3): 656-662. |

| [30] |

LOHAR D P, HARIDAS S, GANTT J S, et al. A transient decrease in reactive oxygen species in roots leads to root hair deformation in the legume-rhizobia symbiosis[J]. New Phytologist, 2007, 173(1): 39-49. |

| [31] |

MUÑOZ V, IBÁÑEZ F, TORDABLE M, et al. Role of reactive oxygen species generation and Nod factors during the early symbiotic interaction between bradyrhizobia and peanut, a legume infected by crack entry[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2015, 118(1): 182-192. |

| [32] |

MATAMOROS M A, DALTON D A, RAMOS J, et al. Biochemistry and molecular biology of antioxidants in the rhizobia-legume symbiosis[J]. Plant Physiology, 2003, 133(2): 499-509. |

| [33] |

VASSE J, DE BILLY F, TRUCHET G. Abortion of infection during the Rhizobium meliloti-alfalfa symbiotic interaction is accompanied by a hypersensitive reaction[J]. The Plant Journal, 1993, 4(3): 555-566. |

| [34] |

Santos R, Hérouart D, Sigaud S, et al. Oxidative burst in alfalfa-Sinorhizobium meliloti symbiotic interaction[J]. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 2001, 14(1): 86-89. |

| [35] |

D'HAEZE W, DE RYCKE R, MATHIS R, et al. Reactive oxygen species and ethylene play a positive role in lateral root base nodulation of a semiaquatic legume[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2003, 100(20): 11789-11794. |

| [36] |

ZEPEDA I, SÁNCHEZ-LÓPEZ R, KUNKEL J G, et al. Visualization of highly dynamic F-actin plus ends in growing Phaseolus vulgaris root hair cells and their responses to Rhizobium etli nod factors[J]. Plant and Cell Physiology, 2014, 55(3): 580-592. |

| [37] |

SHAILES S, OLDROYD G E D. Biological Nitrogen Fixation[M]. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2015: 533-546.

|

| [38] |

LISZKAY A, KENK B, SCHOPFER P. Evidence for the involvement of cell wall peroxidase in the generation of hydroxyl radicals mediating extension growth[J]. Planta, 2003, 217(4): 658-667. |

| [39] |

RUBIO M C, JAMES E K, CLEMENTE M R, et al. Localization of superoxide dismutases and hydrogen peroxide in legume root nodules[J]. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 2004, 17(12): 1294-1305. |

| [40] |

WISNIEWSKI J P, RATHBUN E A, KNOX J P, et al. Involvement of diamine oxidase and peroxidase in insolubilization of the extracellular matrix:implications for pea nodule initiation by Rhizobium leguminosarum[J]. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 2000, 13(4): 413-420. |

| [41] |

ANDRIO E, MARINO D, MARMEYS A, et al. Hydrogen peroxide-regulated genes in the Medicago truncatula-Sinorhizobium meliloti symbiosis[J]. New Phytologist, 2013, 198(1): 179-189. |

| [42] |

PELEG-GROSSMAN S, VOLPIN H, LEVINE A. Root hair curling and Rhizobium infection in Medicago truncatula are mediated by phosphatidylinositide-regulated endocytosis and reactive oxygen species[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2007, 58(7): 1637-1649. |

| [43] |

MONTIEL J, NAVA N, CÁRDENAS L, et al. A Phaseolus vulgaris NADPH oxidase gene is required for root infection by rhizobia[J]. Plant and Cell Physiology, 2012, 53(10): 1751-1767. |

| [44] |

ARTHIKALA M K, SÁNCHEZ-LÓPEZ R, NAVA N, et al. RbohB, a Phaseolus vulgaris NADPH oxidase gene, enhances symbiosome number, bacteroid size, and nitrogen fixation in nodules and impairs mycorrhizal colonization[J]. New Phytologist, 2014, 202(3): 886-900. |

| [45] |

JAMET A, MANDON K, PUPPO A, et al. H2O2 is required for optimal establishment of the Medicago sativa/Sinorhizobium meliloti symbiosis[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 2007, 189(23): 8741-8745. DOI:10.1128/JB.01130-07 |

| [46] |

DAVIES J M. Annexin-mediated calcium signalling in plants[J]. Plants, 2014, 3(1): 128-140. |

| [47] |

WILKINS K A, MATTHUS E, SWARBRECK S M, et al. Calcium-mediated abiotic stress signaling in roots[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2016, 7: 1296. |

| [48] |

CARRASCO-CASTILLA J, ORTEGA-ORTEGA Y, JÁUREGUI-ZÚÑIGA D, et al. Down-regulation of a Phaseolus vulgaris annexin impairs rhizobial infection and nodulation[J]. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 2018, 153: 108-119. DOI:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.05.016 |

| [49] |

VAN DE VELDE W, ZEHIROV G, SZATMARI A, et al. Plant peptides govern terminal differentiation of bacteria in symbiosis[J]. Science, 2010, 327(5969): 1122-1126. DOI:10.1126/science.1184057 |

| [50] |

MUÑOZ V, IBÁÑEZ F, FIGUEREDO M S, et al. An oxidative burst and its attenuation by bacterial peroxidase activity is required for optimal establishment of the Arachis hypogaea-Bradyrhizobium sp. symbiosis[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2016, 121(1): 244-253. |

| [51] |

NILES B J, JOSLIN A C, FRESQUES T, et al. TOR complex 2-Ypk1 signaling maintains sphingolipid homeostasis by sensing and regulating ROS accumulation[J]. Cell Reports, 2014, 6(3): 541-552. |

| [52] |

NANJAREDDY K, BLANCO L, ARTHIKALA M K, et al. A legume TOR protein kinase regulates Rhizobium symbiosis and is essential for infection and nodule development[J]. Plant Physiology, 2016, 172(3): 2002-2020. |

| [53] |

MARINO D, HOHNJEC N, K STER H, et al. Evidence for transcriptional and post-translational regulation of sucrose synthase in pea nodules by the cellular redox state[J]. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 2008, 21(5): 622-630. |

| [54] |

DODD A N, KUDLA J, SANDERS D. The language of calcium signaling[J]. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 2010, 61: 593-620. |

| [55] |

ZHANG C, BOUSQUET A, HARRIS J M. Abscisic acid and lateral root organ defenctive/numerous infections and polyphenolics modulate root elongation via reactive oxygen species in Medicago truncatula[J]. Plant Physiology, 2014, 166(2): 644-658. |

| [56] |

FOREMAN J, DEMIDCHIK V, BOTHWELL J H F, et al. Reactive oxygen species produced by NADPH oxidase regulate plant cell growth[J]. Nature, 2003, 422(6930): 442-446. DOI:10.1038/nature01485 |

| [57] |

OGASAWARA Y, KAYA H, HIRAOKA G, et al. Synergistic activation of the Arabidopsis NADPH oxidase AtrbohD by Ca2+ and phosphorylation[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2008, 283(14): 8885-8892. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M708106200 |

| [58] |

QIN Y M, ZHU Y X. How cotton fibers elongate:A tale of linear cell-growth mode[J]. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 2011, 14(1): 106-111. DOI:10.1016/j.pbi.2010.09.010 |

| [59] |

ZHANG F, JIN X X, WANG L, et al. A cotton annexin affects fiber elongation and secondary cell wall biosynthesis associated with Ca2+ influx, ROS homeostasis, and actin filament reorganization[J]. Plant Physiology, 2016, 171(3): 1750-1770. |

| [60] |

TORRES M A, DANGL J L. Functions of the respiratory burst oxidase in biotic interactions, abiotic stress and development[J]. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 2005, 8(4): 397-403. |

| [61] |

MORI I C, SCHROEDER J I. Reactive oxygen species activation of plant Ca2+ channels. A signaling mechanism in polar growth, hormone transduction, stress signaling, and hypothetically mechanotransduction[J]. Plant Physiology, 2004, 135(2): 702-708. |

| [62] |

RICHARDS S L, LAOHAVISIT A, MORTIMER J C, et al. Annexin 1 regulates the H2O2-induced calcium signature in Arabidopsis thaliana roots[J]. The Plant Journal, 2014, 77(1): 136-145. |

| [63] |

KWAK J M, MORI I C, PEI Z M, et al. NADPH oxidase AtrbohD and AtrbohF genes function in ROS-dependent ABA signaling in Arabidopsis[J]. The EMBO Journal, 2003, 22(11): 2623-2633. |

| [64] |

JIANG M, ZHANG J. Cross-talk between calcium and reactive oxygen species originated from NADPH oxidase in abscisic acid-induced antioxidant defence in leaves of maize seedlings[J]. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2003, 26(6): 929-939. |

| [65] |

TAKAHASHI S, KIMURA S, KAYA H, et al. Reactive oxygen species production and activation mechanism of the rice NADPH oxidase OsRbohB[J]. The Journal of Biochemistry, 2012, 152(1): 37-43. |

| [66] |

KLÜSENER B, YOUNG J J, MURATA Y, et al. Convergence of calcium signaling pathways of pathogenic elicitors and abscisic acid in Arabidopsis guard cells[J]. Plant Physiology, 2002, 130(4): 2152-2163. |

| [67] |

OLDROYD G E D, DOWNIE J A. Calcium, kinases and nodulation signalling in legumes[J]. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2004, 5(7): 566-576. |

| [68] |

ODA T, HASHIMOTO H, KUWABARA N, et al. Structure of the N-terminal regulatory domain of a plant NADPH oxidase and its functional implications[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2010, 285(2): 1435-1445. |

| [69] |

GLYAN'KO A K, ISHCHENKO A A. Influence of rhizobial (Rhizobium leguminosarum) inoculation and calcium ions on the NADPH oxidase activity in roots of etiolated pea (Pisum sativum L.) seedlings[J]. Applied Biochemistry and Microbiology, 2013, 49(3): 215-219. |

| [70] |

TÓTH K, STACEY G. Does plant immunity play a critical role during initiation of the legume-rhizobium symbiosis?[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2015, 6: 401. |

| [71] |

DAMIANI I, PAULY N, PUPPO A, et al. Reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide control early steps of the Legume-Rhizobium symbiotic interaction[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2016, 7: 454. |

| [72] |

LIANG Y, CAO Y R, TANAKA K, et al. Nonlegumes respond to rhizobial Nod factors by suppressing the innate immune response[J]. Science, 2013, 341(6152): 1384-1387. DOI:10.1126/science.1242736 |

| [73] |

MATAMOROS M A, SAIZ A, PEÑUELAS M, et al. Function of glutathione peroxidases in legume root nodules[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2015, 66(10): 2979-2990. |

| [74] |

JAMET A, SIGAUD S, VAN DE SYPE G, et al. Expression of the bacterial catalase genes during Sinorhizobium meliloti-Medicago sativa symbiosis and their crucial role during the infection process[J]. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 2003, 16(3): 217-225. |

| [75] |

SANTOS R, H ROUART D, PUPPO A, et al. Critical protective role of bacterial superoxide dismutase in Rhizobium-legume symbiosis[J]. Molecular Microbiology, 2000, 38(4): 750-759. |

| [76] |

GOURION B, BERRABAH F, RATET P, et al. Rhizobium-legume symbioses:The crucial role of plant immunity[J]. Trends in Plant Science, 2015, 20(3): 186-194. |

| [77] |

BOSCARI A, MEILHOC E, CASTELLA C, et al. Which role for nitric oxide in symbiotic N2-fixing nodules:Toxic by-product or useful signaling/metabolic intermediate?[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2013, 4: 384. |

| [78] |

SCHELER C, DURNER J, ASTIER J. Nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in plant biotic interactions[J]. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 2013, 16(4): 534-539. |

| [79] |

HICHRI I, BOSCARI A, CASTELLA C, et al. Nitric oxide:A multifaceted regulator of the nitrogen-fixing symbiosis[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2015, 66(10): 2877-2887. |

| [80] |

HICHRI I, MEILHOC E, BOSCARI A, et al. Nitric oxide:Jack-of-all-trades of the nitrogen-fixing symbiosis?[J]. Advances in Botanical Research, 2016, 77: 193-218. DOI:10.1016/bs.abr.2015.10.014 |

| [81] |

YUN B W, FEECHAN A, YIN M H, et al. S-nitrosylation of NADPH oxidase regulates cell death in plant immunity[J]. Nature, 2011, 478(7368): 264-268. |

| [82] |

VANDELLE E, DELLEDONNE M. Peroxynitrite formation and function in plants[J]. Plant Science, 2011, 181(5): 534-539. |

| [83] |

BLANQUET P, SILVA L, CATRICE O, et al. Sinorhizobium meliloti controls nitric oxide-mediated post-translational modification of a Medicago truncatula nodule protein[J]. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 2015, 28(12): 1353-1363. DOI:10.1094/MPMI-05-15-0118-R |

| [84] |

LIANG Y, T TH K, CAO Y R, et al. Lipochitooligosaccharide recognition:An ancient story[J]. New Phytologist, 2014, 204(2): 289-296. |

2019, Vol. 27

2019, Vol. 27