2. 北京师范大学生命科学学院/生物多样性与生态工程教育部重点实验室 北京 100875;

3. 中山大学生命科学学院/有害生物控制与资源利用国家重点实验室 广州 510275

2. College of Life Sciences, Beijing Normal University/Key Laboratory for Biodiversity Science and Ecological Engineering, Ministry of Education, Beijing 100875, China;

3. College of Life Sciences, Sun Yat-Sen University/State Key Laboratory of Biocontrol and Resource Utilization, Guangzhou 510275, China

据估计, 世界人口总数将于2040年达到80亿, 粮食安全问题将持续存在[1]。达尔文农学理论(Darwinian agriculture)认为, 引入进化思想可以为农业育种提供一个崭新的视角[2]。早在19世纪, 达尔文就在《物种起源》中指出, 自然选择和人工选择是两种具有不同目标的进化动力[3]; 自然选择最大化作物个体适合度, 而人工选择的目标则是提升作物群体表现, 比如单位面积籽粒产量。作物群体中, 高茎秆、大根系等变异使植株在竞争有限资源时具有较高个体竞争力, 因此生产更多种子, 从而增加在种群中的频率。由于单位土地面积上资源总量一定, 营养生长和繁殖生长之间必然存在权衡[4], 故营养器官的冗余生长不利于群体产量。基于达尔文农学理论, 可以利用个体竞争力和产量之间的权衡关系——选育个体竞争力弱化的、营养器官冗余减小的基因型, 以期提高农业产量[2, 5-8]。

事实上, 人们在培育高产作物时已经无意识地利用了这种权衡关系。绿色革命中的矮秆品种的成功普及即是一个鲜明的例证:原本用于茎秆生产的光合产物更多投入到种子生产, 因此大幅度提高了产量[9]。对个体竞争力的无意识弱化也发生在地下。美国玉米(Zea mays)在过去的100年育种历程中次生根数量减少、根系构型发生了改变[10]。中国春小麦(Triticum aestivum)现代品种相比古老品种, 由于减少了根系冗余得以提高产量[6, 11-13]。另一方面, 大量研究证明, 当同一基因型或同品种个体之间竞争总量一定的地下资源时, 会产生可塑性的根系增生[14-17], 而根系增生以作物产量降低为代价, 这被称为根系竞争的“公地悲剧”(tragedy of the commons)。因此, 除了减少根系冗余, 减少或者消除根系竞争导致的根系增生(也是减弱个体竞争力), 也可以成为农业上提高产量的一种有效途径[18]。但关于根系如何响应邻株根系的存在, 目前为止并没有一致结论[19]。也有研究表明, 根系竞争不会导致根系增生[20-21]。另外, 之前的研究较少从育种的角度解读根系竞争对农业产量的影响, 对于人工育种是否已经无意识地影响作物根系竞争效应, 截至目前相关研究很少[22-23]。因此, 本研究选用全球第三大粮食作物小麦的两个不同年代品种, 考察春小麦是否存在根系增生, 以及育种如何影响根系竞争效应。已有的根系竞争的“公地悲剧”研究一般采用分根法, 即无根系竞争采用两个植株分别在两个花盆中单独生长, 根系竞争则采用两个植株的根系分别跨越两个相邻花盆竞争生长[14-16], 这导致竞争处理中植株的根系生长空间是无竞争处理的2倍, 因此根系竞争效应可能与根系生长空间混淆[24-25]。也有研究在排除根系生长空间的影响后, 仍发现根系竞争导致根系增生[26-28]。有研究用尼龙网隔离不同植株根系, 在允许根系分泌物通过的同时限制了根系生长范围, 排除了根系生长空间这一干扰因素[29]。但另一方面, 尼龙隔离也允许水和营养物质的流动, 这可能会增加植株可利用营养总量。本研究除了设置尼龙隔离和无竞争塑料隔离, 还设置了有竞争塑料隔离以及2倍营养处理。1倍营养-无竞争塑料隔离和2倍营养-有竞争塑料隔离相比, 单株根系可利用生长空间和单株可获得营养量均一致, 可有效研究根系竞争效应。本研究选取春小麦古老品种‘和尚头’和现代品种‘92-46’, 通过设置不同根系隔离处理, 主要解答以下两个关键问题: 1)春小麦根系竞争如何影响各部分生物量及资源分配(根系竞争效应)? 2)两个不同年代春小麦品种根系竞争效应有何差异(根系竞争效应×品种效应)?

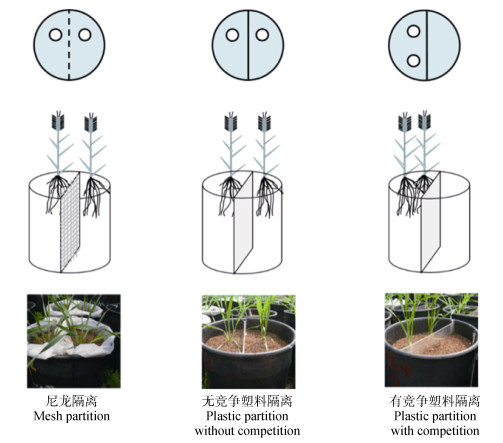

1 材料与方法 1.1 试验设计盆栽试验于2010年5—8月在北京师范大学生物园(116°2′E, 39°6′N, 海拔54 m)开展。设置隔离、营养和品种3个因子。3种隔离处理如图 1所示:尼龙隔离、无竞争塑料隔离、有竞争塑料隔离。尼龙隔离中, 以尼龙布(400目)将聚乙烯花盆(直径25 cm, 高38 cm)均分为两部分。塑料隔离中, 用塑料板(长37 cm, 宽24.5 cm)将花盆均分为两部分, 并用密封胶填补边缘缝隙。尼龙隔离和无竞争塑料隔离中, 2株春小麦分布在隔离两侧; 有竞争塑料隔离中, 2株春小麦分布在同侧。所有处理中两株春小麦间距均为9 cm, 以保证地上竞争一致。2倍营养-有竞争塑料隔离与1倍营养-无竞争塑料隔离相比, 即根系竞争处理与无根系竞争处理相比, 单株根系可利用生长空间和单株可获得营养量一致(表 1)。种植基质为蛭石, 以浇营养液频率设置两个营养水平:每隔6 d施用1次营养液的为2倍营养液处理, 每隔12 d施用1次营养液的为1倍营养处理, 营养液均为0.2 g·L–1的花多多1号通用肥(N-P-K: 20 g-20 g-20 g)水溶液。

|

图 1 不同隔离处理示意图 Fig. 1 Illustration for different partition treatments |

| 表 1 根系竞争处理和无根系竞争处理下春小麦生长条件比较 Table 1 Comparison of growing conditions of wheat plants with root competition and without root competition treatments |

供试品种为春小麦‘和尚头’和‘92-46’。品种‘和尚头’是中国甘肃省地方品种, 于20世纪40年代到70年代间广泛种植。现代品种‘92-46’是甘肃省2000年育成品种, 也在当地广泛种植。这两个品种生长期相近, 但‘和尚头’无麦芒故可以从形态上区分。每种处理重复10次, 共120盆。待春小麦成熟后, 收获每株春小麦地上部分, 65 ℃烘干称重; 将种子从穗中分离出来并称重。用清水将根系冲洗干净, 65 ℃烘干称重。

1.2 数据分析用ANOVA分析隔离、营养和品种对各部分生物量及总生物量的影响; 合并1倍营养和2倍营养再分析隔离、品种及交互作用对各部分生物量及总生物量的影响; 用ANOVA分析根系竞争(2倍营养-有竞争塑料隔离和1倍营养-无竞争塑料隔离)、品种及交互作用对各部分生物量及总生物量的影响。用Tukey多重比较对不同处理间均值进行差异显著性分析。为了满足残差正态分布和方差齐性, 所有生物量数据使用前进行对数转换。以上数据分析均使用SPSS 22.0进行。

为了消除单株可获得营养量(即植株大小效应)对结果的影响, 用标准化主轴回归(standardized major axis regression, SMA)进行各器官生物量与总生物量之间的回归分析[18, 30]。用post-hoc多重比较对不同处理间回归斜率和截距进行差异显著性分析。以上分析均使用软件‘Standardized Major Axis Tests and Routines (SMATR)2.0’进行[31]。

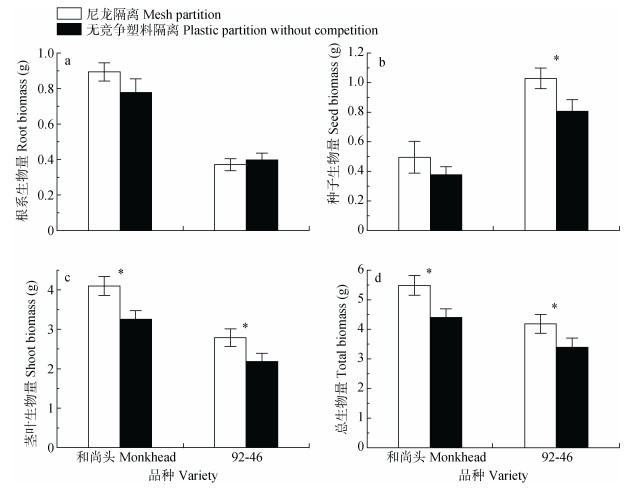

2 结果与分析 2.1 根系竞争对不同年代春小麦品种生物量的影响 2.1.1 尼龙隔离与无竞争塑料隔离的比较营养因素对两品种各器官生物量均无显著影响, 因此合并1倍营养和2倍营养再做方差分析。不同隔离方式对两品种的根系生物量均无显著影响(图 2a)。‘和尚头’在尼龙隔离下的种子生物量与无竞争塑料隔离无显著差异, 但‘92-46’在尼龙隔离下的种子生物量显著高于无竞争塑料隔离(图 2b)。两品种在尼龙隔离下的茎叶生物量和总生物量都显著高于无竞争塑料隔离(图 2c-d)。‘和尚头’的根系生物量、茎叶生物量和总生物量均显著大于‘92-46’, 而种子生物量显著小于‘92-46’(图 2)。

|

图 2 尼龙隔离和无竞争塑料隔离下春小麦品种‘和尚头’和‘92-46’的生物量 Fig. 2 Biomasses of spring wheat varieties 'Monkhead' and '92-46' under mesh partition and plastic partition without root competition 柱状图显示均值±标准误差。*表示尼龙隔离和无竞争塑料隔离在0.05水平(双侧)上差异显著。The data are mean ± SE. * means a significant difference between mesh partition and plastic partition without competition at 0.05 level (bilateral). |

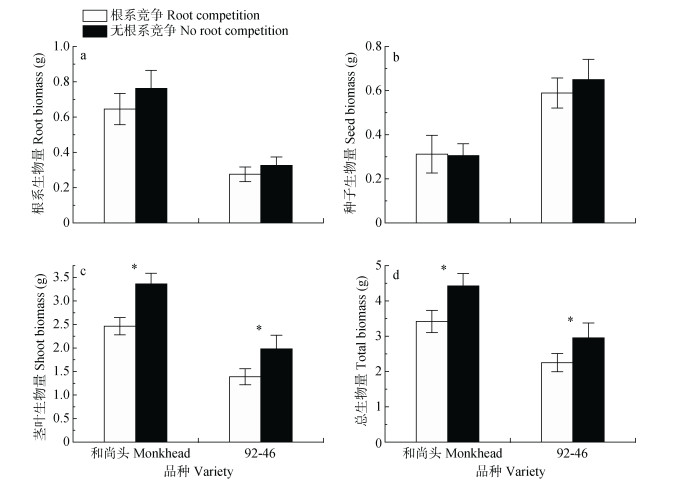

根系竞争对两品种的根系生物量和种子生物量均无显著影响(图 3a-b), 但显著降低了两品种的茎叶生物量和总生物量(图 3c-d), 其中对于‘92-46’的茎叶生物量的影响是边缘显著的(F=3.14, P=0.093)。‘和尚头’的根系生物量、茎叶生物量和总生物量均大于‘92-46’, 而种子生物量小于‘92-46’(图 3)。

|

图 3 根系竞争处理和无根系竞争处理下春小麦品种‘和尚头’和‘92-46’的生物量 Fig. 3 Biomasses of spring wheat varieties 'Monkhead' and '92-46'with and without root competition 柱状图显示均值±标准误差。*表示根系竞争处理和无根系竞争处理在0.05水平(双侧)上差异显著。The data are mea ± SE. * means a significant difference between with and without root competition treatments at 0.05 level (bilateral). |

对于任一品种在任一隔离设置下, 营养都不影响春小麦器官生物量与总生物量之间的回归关系, 因此把1倍营养和2倍营养合并之后再做SMA分析, 并通过比较斜率和截距来判断隔离或品种对资源分配的影响[18, 30-32]。对于古老品种‘和尚头’, 根系竞争对各回归关系的斜率和截距均无显著影响(表 2)。对于现代品种‘92-46’, 根系竞争显著降低了根系生物量-全株总生物量回归关系的截距, 但对其他回归关系的斜率和截距均无显著影响(表 2)。SMA分析显示出资源分配的品种差异:两个品种的根系生物量-全株总生物量回归关系无显著差异; ‘和尚头’的种子生物量-全株总生物量回归关系的斜率比‘92-46’大, 但截距比‘92-46’小; ‘和尚头’的茎叶生物量-全株生物量回归关系的斜率和‘92-46’无差异, 但截距比‘92-46’大(表 2)。

| 表 2 尼龙隔离和无竞争塑料隔离下春小麦品种‘和尚头’和‘92-46’各器官生物量与全株总生物量之间的标准主轴回归分析 Table 2 Standardized major axis regressions of biomass between different organs and whole plant for spring wheat varieties 'Monkhead' and '92-46' under mesh partition and plastic partition without competition |

根系竞争对两品种的各个回归关系的斜率和截距均无显著影响(表 3)。SMA分析显示出资源分配的品种差异:有根系竞争时, 两个品种的根系生物量-全株总生物量回归关系无显著差异; 但无根系竞争时, ‘和尚头’的斜率大于‘92-46’。‘和尚头’的种子生物量-全株总生物量回归关系的斜率比‘92-46’大, 但截距比‘92-46’小; ‘和尚头’的茎叶生物量-全株总生物量回归关系的斜率和‘92-46’无差异, 但截距比‘92-46’大(表 3)。

| 表 3 根系竞争处理和无根系竞争处理下‘和尚头’和‘92-46’各器官生物量与全株总生物量之间的标准主轴回归分析 Table 3 Standardized major axis regressions of biomass between different organs and whole plant for spring wheat varieties 'Monkhead' and '92-46' with and without root competition |

本研究通过设置不同根系竞争情境(尼龙隔离与无竞争塑料隔离, 根系竞争处理与无根系竞争处理)研究根系竞争效应。结果显示, 不管是‘和尚头’还是‘92-46’, 春小麦品种内根系竞争均没有导致根系增生或者根系资源分配提高(图 2、图 3, 表 2、表 3)。这表明春小麦的根系竞争没有导致所谓的“公地悲剧”。研究表明, 邻近植株根系的存在除了可以导致根系增生[15, 20, 33-34], 还可以导致根系生物量减少[21, 35-37]或者没有变化[38-39]。没有变化的原因可能是植株无法识别邻株的存在, 或者能够识别但不能区分自己根系与邻株根系[35]。根系竞争试验的meta分析表明, 种内根系竞争策略的选择是由该物种的进化历史和当前生存环境共同决定的[40], 并且根系增生现象多出现于豆科(Fabaceae)植物中。根系竞争的“公地悲剧”现象是地下资源依赖的, 当地下资源更稀缺时, 植物有更大概率采取根系增生策略, 因为此时地下资源的竞争对于个体生存更重要[20, 40]。同样用‘和尚头’和‘92-46’这两个品种, 后续研究发现当设置差异明显的两个水肥条件时, 高水肥条件下根系竞争不影响资源分配, 但低水肥条件下根系竞争导致‘和尚头’茎叶资源分配增多且繁殖分配下降[41]。除了地下资源, 土壤中的其他诸多因素都会影响根系竞争行为[38, 42-43]。

需要注意到是, 由于植物生长本身是一个异速生长的过程[18], 异速生长分析(SMA)相比生物量数据及生物量比例数据(根系生物量/总生物量)更能真实反映植物的资源分配策略[18, 32, 44-45]。本研究结果显示, 尼龙隔离下种子生物量(只有现代品种‘92-46’)、茎叶生物量和总生物量大于无竞争塑料隔离, 但异速生长分析显示种子和茎叶资源分配模式均无变化(图 2, 表 2)。这表明茎叶生物量和总生物量的增加并不是由于根系竞争效应, 推测可能是由于尼龙隔离使得植株可获得营养量增加导致[25]。研究结果还显示, 根系竞争处理(2倍营养-有竞争塑料隔离)的茎叶生物量和总生物量小于无根系竞争处理(1倍营养-无竞争塑料隔离), 但异速生长分析显示资源分配模式也没有变化(图 3, 表 3)。这表明茎叶生物量和总生物量的减少也不是由于根系竞争效应导致的。这可能是由于试验实施过程中实际施肥方式导致:即在按2倍关系施加营养之前, 所有处理均施加了两次底肥, 导致根系竞争处理植株实际获得营养量小于无根系竞争处理(表 1)。

虽然根系竞争没有使‘和尚头’和‘92-46’陷入“公地悲剧”, 但仍显示出显著的根系竞争效应及根系竞争×品种交互效应:尼龙隔离下‘92-46’的根系资源分配小于无竞争塑料隔离, 而‘和尚头’无此变化(表 2)。首先, 这一现象表明, 现代品种‘92-46’的根系有一定程度的自我-非我识别能力, 当感知到周围有同品种非我植株时, 能做出调整资源分配的反应。已有研究表明, 植物可以通过地上叶片感知周围环境中红外线/远红外线比例来判断有无竞争者并做出相应反馈[46]。有不少研究发现植物也可以通过根系进行自我-非我识别[22, 36, 47]。其次, 本试验设置中, 尼龙隔离和无竞争塑料隔离下, 相邻植株的根系都没有物理接触, 区别在于根系分泌物, 即尼龙隔离允许根系分泌物穿过尼龙网进而影响邻株, 而无竞争塑料隔离中根系分泌物无法通过。因此我们推测, ‘92-46’对邻株的识别可能是根系分泌物介导的。已有不少研究表明根系分泌物可以介导植株自我-非我识别[22, 36, 47-48]。第三, 现代品种‘92-46’在同品种根系竞争时减少了根系资源分配, 即克制了根系竞争行为; 而‘和尚头’在同品种根系竞争时并无此变化。这表明现代品种相比古老品种, 可能在以高产为目标的育种过程中被无意识选育出一定程度的合作行为。而古老品种在自然选择的作用下以最大化个体竞争力为目标, 不大可能进化出合作行为。达尔文农学认为, 应有意识地通过群体选择来培育个体之间更加合作的基因型, 以提高单位面积产量[49]。本研究结果中‘92-46’根系资源分配的减少也与我们前期研究结果一致:竞争力比较实验中, ‘92-46’相对比例越高, 根系资源分配就越小; 而‘和尚头’的根系资源分配不随相对比例的变化而变化[13], 表明‘92-46’在与同品种个体竞争时更加保守, 降低了对根系的资源投入。

另外, 本研究还揭示了两品种的组成型差异:生物量数据显示‘和尚头’的根系生物量和茎叶生物量均大于‘92-46’, 而种子生物量小于‘92-46’(图 2, 图 3)。SMA分析显示, 大部分情况下‘和尚头’和‘92-46’的根系资源分配并没有显著差异(除无根系竞争处理斜率外), ‘和尚头’的茎叶资源分配显著高于‘92-46’, 而种子资源分配显著低于‘92-46’(表 2, 表 3)。首先, 这一结果表明资源分配在营养生长和繁殖生长间存在权衡。本研究中现代品种‘92-46’繁殖资源分配的提高是由于茎叶资源分配的降低。这符合达尔文农学理论的基本假设:选育个体竞争力弱化的、营养器官冗余减小的基因型, 以期提高农业产量[2, 5-8]。需要说明的是, 该研究只选用了一个古老品种和一个现代品种, 关于育种的影响只是得出初步的、尝试性的结论。但与后续他人研究结果的一致性使该研究结论更加可靠。比如, 研究考察成熟期相近的35个中国春小麦品种, 发现中等竞争力品种的产量比高竞争力品种平均高35%[6]。其次, 这一结果还表明, 资源分配在营养器官上的减少主要体现在茎叶, 而不是根系。之前研究较多是从根系生物量或者根系比例(根系生物量/总生物量)这两个指标上揭示根系冗余的存在[13, 50-52], 易把植株大小对繁殖资源分配的影响与根系竞争导致的繁殖资源分配调整混淆[18]。因此, 之前研究[13]可能高估了‘和尚头’根系冗余的程度, 即部分“冗余”是由于其本身较大的总生物量导致, 并非真正的资源分配策略上的差异。因此, 相对于比较根系生物量或者根系比例这两个点值, 比较不同处理之间的异速生长过程是更优化的研究资源分配问题的途径。

4 结论通过考察两个不同年代春小麦品种在不同根系竞争情境下的生物量及资源分配, 发现春小麦根系竞争并没有导致根系增生的“公地悲剧”现象, 这可能与春小麦本身进化历史有关, 或者是由于地下资源比较充分。另外, 本研究发现相比古老品种‘和尚头’, 现代品种‘92-46’可能发展出一定程度的合作行为, 可能是通过根系分泌物介导识别邻株根系并减少根系资源分配。以高产为目标的作物育种可能无意识选择了个体之间更加合作的基因型, 后续研究应选用更多品种来检验合作行为在现代品种中是否具有普遍性。最后, 本研究揭示了两个品种的组成型差异:现代品种‘92-46’将资源更多分配到繁殖生长, 而古老品种‘和尚头’更多分配到茎叶生长。这支持了达尔文农学理论的基本假设:个体竞争力弱化的、营养器官冗余减小的基因型具有产量提高的潜力。如果能够把对个体竞争力的无意识弱化转化为有意识的选育, 将有助于提高作物产量和应对21世纪的粮食危机。

| [1] |

BROWN L R. World on the Edge:How to Prevent Environmental and Economic Collapse[M]. New York: W. W. Norton, 2011.

|

| [2] |

DENISON R F. Darwinian Agriculture:How Understanding Evolution Can Improve Agriculture[M]. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.

|

| [3] |

DARWIN C R. The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection[M]. New York: Collier, 1859.

|

| [4] |

HARPER J L. Population Biology of Plants[M]. London: Academic Press, 1977.

|

| [5] |

DONALD C M. The breeding of crop ideotypes[J]. Euphytica, 1968, 17(3): 385-403. DOI:10.1007/BF00056241 |

| [6] |

WEINER J, DU Y L, ZHANG C, et al. Evolutionary agroecology:Individual fitness and population yield in wheat (Triticumaestivum)[J]. Ecology, 2017, 98(9): 2261-2266. DOI:10.1002/ecy.1934 |

| [7] |

ZHANG D Y, SUN G J, JIANG X H. Donald's ideotype and growth redundancy:A game theoretical analysis[J]. Field Crops Research, 1999, 61(2): 179-187. |

| [8] |

张大勇, 姜新华. 对于作物生产的生态学思考[J]. 植物生态学报, 2000, 24(3): 383-384. ZHANG D Y, JIANG X H. An ecological perspective on crop production[J]. Acta Phytoecologica Sinica, 2000, 24(3): 383-384. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1005-264X.2000.03.024 |

| [9] |

JENNINGS P R, DE JESUS J JR. Studies on competition in rice Ⅰ. Competition in mixtures of varieties[J]. Evolution, 1968, 22(1): 119-124. |

| [10] |

YORK L M, GALINDO-CASTAÑEDA T, SCHUSSLER J R, et al. Evolution of US maize (Zea mays L.) root architectural and anatomical phenes over the past 100 years corresponds to increased tolerance of nitrogen stress[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2015, 66(8): 2347-2358. DOI:10.1093/jxb/erv074 |

| [11] |

ZHU Y H, WEINER J, YU M X, et al. Evolutionary agroecology:Trends in root architecture during wheat breeding[J]. Evolutionary Applications, 2019, 12(4): 733-743. |

| [12] |

李龙.小麦根系形态及抗旱相关生理性状的遗传解析[D].北京: 中国农业科学院, 2017 LI L. Genetic dissection of root morphology and drought-tolerant related physiological traits in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)[D]. Beijing: Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, 2017 |

| [13] |

ZHU L, ZHANG D Y. Donald's ideotype and growth redundancy:A pot experimental test using an old and a modern spring wheat cultivar[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(7): e70006. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0070006 |

| [14] |

GERSANI M, BROWN J S, O'BRIEN E E, et al. Tragedy of the commons as a result of root competition[J]. Journal of Ecology, 2001, 89(4): 660-669. |

| [15] |

MAINA G G, BROWN J S, GERSANI M. Intra-plant versus inter-plant root competition in beans:Avoidance, resource matching or tragedy of the commons[J]. Plant Ecology, 2002, 160(2): 235-247. |

| [16] |

O'BRIEN E E, GERSANI M, BROWN J S. Root proliferation and seed yield in response to spatial heterogeneity of below- ground competition[J]. New Phytologist, 2005, 168(2): 401-412. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01520.x |

| [17] |

PADILLA F M, MOMMER L, DE CALUWE H, et al. Early root overproduction not triggered by nutrients decisive for competitive success belowground[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(1): e55805. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0055805 |

| [18] |

WEINER J. Allocation, plasticity and allometry in plants[J]. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, 2004, 6(4): 207-215. DOI:10.1078/1433-8319-00083 |

| [19] |

MCNICKLE G G, DEYHOLOS M K, CAHILL J F. Nutrient foraging behaviour of four co-occurring perennial grassland plant species alone does not predict behaviour with neighbours[J]. Functional Ecology, 2016, 30(3): 420-430. |

| [20] |

MCNICKLE G G, BROWN J S. An ideal free distribution explains the root production of plants that do not engage in a tragedy of the commons game[J]. Journal of Ecology, 2014, 102(4): 963-971. |

| [21] |

SCHENK H J, CALLAWAY R M, MAHALL B E. Spatial root segregation:Are plants territorial?[J]. Advances in Ecological Research, 1999, 28: 145-180. DOI:10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60032-X |

| [22] |

CHEN B J W, DURING H J, ANTEN N P R. Detect thy neighbor:Identity recognition at the root level in plants[J]. Plant Science, 2012, 195: 157-167. DOI:10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.07.006 |

| [23] |

SEMCHENKO M, ZOBEL K. The effect of breeding on allometry and phenotypic plasticity in four varieties of oat (Avena sativa L.)[J]. Field Crops Research, 2005, 93(2/3): 151-168. |

| [24] |

HESS L, DE KROON H. Effects of rooting volume and nutrient availability as an alternative explanation for root self/non-self discrimination[J]. Journal of Ecology, 2007, 95(2): 241-251. |

| [25] |

SCHENK H J. Root competition:Beyond resource depletion[J]. Journal of Ecology, 2006, 94(4): 725-739. |

| [26] |

FALIK O, REIDES P, GERSANI M, et al. Self/non-self discrimination in roots[J]. Journal of Ecology, 2003, 91(4): 525-531. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2745.2003.00795.x |

| [27] |

GRUNTMAN M, NOVOPLANSKY A. Physiologically mediated self/non-self discrimination in roots[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2004, 101(11): 3863-3867. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0306604101 |

| [28] |

SEMCHENKO M, JOHN E A, HUTCHING M J. Effects of physical connection and genetic identity of neighbouring ramets on root-placement patterns in two clonal species[J]. New Phytologist, 2007, 176(3): 644-654. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02211.x |

| [29] |

SEMCHENKO M, HUTCHINGS M J, JOHN E A. Challenging the tragedy of the commons in root competition:Confounding effects of neighbor presence and substrate volume[J]. Journal of Ecology, 2007, 95(2): 252-260. |

| [30] |

MÜLLER I, SCHMID B, WEINER J. The effect of nutrient availability on biomass allocation patterns in 27 species of herbaceous plants[J]. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, 2000, 3(2): 115-127. DOI:10.1078/1433-8319-00007 |

| [31] |

FALSTER D S, WARTON D I, WRIGHT I J. User's guide to smatr: Standardised major axis tests & routines version 2.0, Copyright 2006[EB/OL].[2019-10-23]. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242318498_User's_guide_to_SMATR_Standard-ised_Major_Axis_Tests_Routines_Version_20_Copyright_2006

|

| [32] |

WEINER J, ROSENMEIER L, MASSONI E S, et al. Is reproductive allocation in Senecio vulgaris plastic?[J]. Botany, 2009, 87(5): 475-481. |

| [33] |

LANG at J K S, KIRUI B K Y, SKOV M W, et al. Species mixing boosts root yield in mangrove trees[J]. Oecologia, 2013, 172(1): 271-278. DOI:10.1007/s00442-012-2490-x |

| [34] |

SEMCHENKO M, ZOBEL K, HUTCHINGS M J. To compete or not to compete:An experimental study of interactions between plant species with contrasting root behaviour[J]. Evolutionary Ecology, 2010, 24(6): 1433-1445. DOI:10.1007/s10682-010-9401-6 |

| [35] |

CAHILL J F JR, MCNICKLE G G. The behavioral ecology of nutrient foraging by plants[J]. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 2011, 42(1): 289-311. DOI:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145006 |

| [36] |

DUDLEY S A, FILE A L. Kin recognition in an annual plant[J]. Biology Letters, 2007, 3(4): 435-438. DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0232 |

| [37] |

MURPHY K M, DAWSON J C, JONES S S. Relationship among phenotypic growth traits, yield and weed suppression in spring wheat landraces and modern cultivars[J]. Field Crops Research, 2008, 105(1/2): 107-115. |

| [38] |

LITAV M, HARPER J L. A method for studying spatial relationships between the root systems of two neighbouringplants[J]. Plant and Soil, 1967, 26(2): 389-392. DOI:10.1007/BF01880190 |

| [39] |

NOVOPLANSKY A. Picking battles wisely:Plant behaviour under competition[J]. Plant Cell & Environment, 2009, 32(6): 726-741. |

| [40] |

SMYČKA J, HERBEN T. Phylogenetic patterns of tragedy of commons in intraspecific root competition[J]. Plant and Soil, 2017, 417(1/2): 87-97. |

| [41] |

朱莉.根系竞争和资源条件下对两品种春小麦生长繁殖的影响[D].北京: 北京师范大学, 2013 ZHU L. Effects of root competition and resource availability on the performance of two spring wheat varieties[D]. Beijing: Beijing Normal University, 2013 |

| [42] |

CAHILL J F JR, MCNICKLE G G, HAAG J J, et al. Plants integrate information about nutrients and neighbors[J]. Science, 2010, 328(5986): 1657. DOI:10.1126/science.1189736 |

| [43] |

FANG Y, LIU L, XU B C, et al. The relationship between competitive ability and yield stability in an old and a modern winter wheat cultivar[J]. Plant and Soil, 2011, 347(1/2): 7-23. |

| [44] |

GUO H, WEINER J, MAZER S, et al. Reproductive allometry in pedicularis species changes with elevation[J]. Journal of Ecology, 2012, 100(2): 452-458. |

| [45] |

QIN X, NIKLAS K J, QI L, et al. The effects of domestication on the scaling of below-vs. aboveground biomass in four selected wheat (Triticum; Poaceae) genotypes[J]. American Journal of Botany, 2012, 99(6): 1112-1117. DOI:10.3732/ajb.1100366 |

| [46] |

BOCCALANDRO H E, PLOSCHUK E L, YANOVSKY M J, et al. Increased phytochrome B alleviates density effects on tuber yield of field potato crops[J]. Plant Physiology, 2003, 133(4): 1539-1546. DOI:10.1104/pp.103.029579 |

| [47] |

FANG S Q, CLARK R T, ZHENG Y, et al. Genotypic recognition and spatial responses by rice roots[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013, 110(7): 2670-2675. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1222821110 |

| [48] |

BIEDRZYCKIM L, JILANY T A, DUDLEY S A, et al. Root exudates mediate kin recognition in plants[J]. Communicative & Integrative Biology, 2010, 3(1): 28-35. |

| [49] |

WEINER J, ANDERSEN S B, WILLE W K M, et al. Evolutionary agroecology:The potential for cooperative, high density, weed-suppressing cereals[J]. Evolutionary Applications, 2010, 3(5/6): 473-479. |

| [50] |

PASSIOURA J B. Roots and drought resistance[J]. Agricultural Water Management, 1983, 7(1/3): 265-280. |

| [51] |

SIDDIQUE K H M, BELFORD R K, TENNANT D. Root:shoot ratios of old and modern, tall and semi-dwarf wheats in a Mediterranean environment[J]. Plant and Soil, 1990, 121(1): 89-98. DOI:10.1007/BF00013101 |

| [52] |

张荣, 张大勇. 半干旱区春小麦不同年代品种根系生长冗余的比较实验研究[J]. 植物生态学报, 2000, 24(3): 298-303. ZHANG R, ZHANG D Y. A comparative study on root redundancy in spring wheat varieties released in different years in semi-arid areas[J]. Acta Phytoecologica Sinica, 2000, 24(3): 298-303. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1005-264X.2000.03.009 |

2020, Vol. 28

2020, Vol. 28